ADMIRAL RAPHAEL SEMMES CAMP #11

SONS OF CONFEDERATE VETERANS

MOBILE, ALABAMA

us ships named in honor of

the state of alabama

In addition to the immortal CSS Alabama, many ships of the US Navy carried the name of the state of Alabama. Here are descriptions of those ships.

Alabama the first

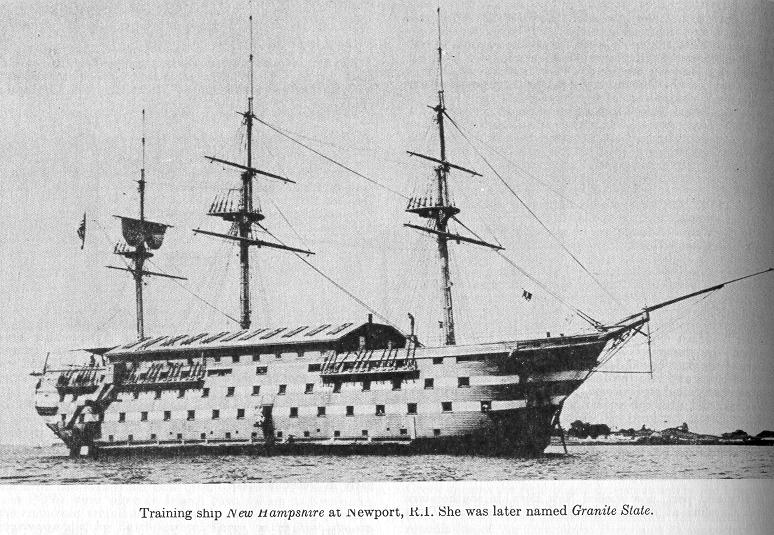

new hampshire (LATER)

the granite state (LATER STILL)

Alabaman-one of the "nine ships to rate not less than 74 guns each" authorized by Congress on 29 April 1816—was laid down in June 1819 at the Portsmouth (N.H.) Navy Yard. In keeping with the policy of the 74-gun ships-of-the-line being maintained in a state of readiness for launch, Alabama remained on the stocks at Portsmouth for almost four decades, in a state of preservation—much like part of a "mothball fleet" of post-World War II years. Needed for service during the Civil War, the ship was completed, but her name was changed to New Hampshire (q.v.) on 28 October 1863.

New Hampshire sailed from Portsmouth 15 June and relieved sister ship Vermont 29 July 1864 as store and depot ship at Port Royal, S.C., and served there through the end of the Civil War. She returned to Norfolk 8 June 1866, serving as a receiving ship there until 10 May 1876 when she sailed back to Port Royal. She resumed duty at Norfolk in 1881 but soon shifted to Newport, R.I. She became flagship of Commodore Stephen B. Luce’s newly formed Apprentice Training Squadron, marking the commencement of an effective apprentice training program for the Navy.

New Hampshire was towed from Newport to New London, Conn., in 1891 and was receiving ship there until decommissioned 5 June 1892. The following year she was loaned as a training ship for the New York State Naval Militia which was to furnish nearly a thousand officers and men to the Navy during the Spanish-American War.

New Hampshire was renamed Granite State 30 November 1904 to free the name New Hampshire for a newly authorized battleship. Stationed in the Hudson River, she continued training service throughout the years leading to World War I when State naval militia were practically the only trained and equipped men available to the Navy for immediate service. They were mustered into the Navy as National Naval Volunteers. Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels wrote in his Our Navy at War: “Never again will men dare riducule the Volunteer, the Reservist, the man who in a national crisis lays aside civilian duty to become a soldier or sailor—They fought well. They died well. They have left in deeds and words a record that will be an inspiration to unborn generations.”

Granite State served the New York State Militia until she caught fire and sank at her pier in the Hudson River 23 May 1921. Her hull was sold for salvage 19 August 1921 to the Mulholland Machinery Corp. Refloated in July 1922, she and was taken in tow to the Bay of Fundy. The towline parted during a storm, she again caught fire and sank off Half Way Rock in Massachusetts Bay

New Hampshire sailed from Portsmouth 15 June and relieved sister ship Vermont 29 July 1864 as store and depot ship at Port Royal, S.C., and served there through the end of the Civil War. She returned to Norfolk 8 June 1866, serving as a receiving ship there until 10 May 1876 when she sailed back to Port Royal. She resumed duty at Norfolk in 1881 but soon shifted to Newport, R.I. She became flagship of Commodore Stephen B. Luce’s newly formed Apprentice Training Squadron, marking the commencement of an effective apprentice training program for the Navy.

New Hampshire was towed from Newport to New London, Conn., in 1891 and was receiving ship there until decommissioned 5 June 1892. The following year she was loaned as a training ship for the New York State Naval Militia which was to furnish nearly a thousand officers and men to the Navy during the Spanish-American War.

New Hampshire was renamed Granite State 30 November 1904 to free the name New Hampshire for a newly authorized battleship. Stationed in the Hudson River, she continued training service throughout the years leading to World War I when State naval militia were practically the only trained and equipped men available to the Navy for immediate service. They were mustered into the Navy as National Naval Volunteers. Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels wrote in his Our Navy at War: “Never again will men dare riducule the Volunteer, the Reservist, the man who in a national crisis lays aside civilian duty to become a soldier or sailor—They fought well. They died well. They have left in deeds and words a record that will be an inspiration to unborn generations.”

Granite State served the New York State Militia until she caught fire and sank at her pier in the Hudson River 23 May 1921. Her hull was sold for salvage 19 August 1921 to the Mulholland Machinery Corp. Refloated in July 1922, she and was taken in tow to the Bay of Fundy. The towline parted during a storm, she again caught fire and sank off Half Way Rock in Massachusetts Bay

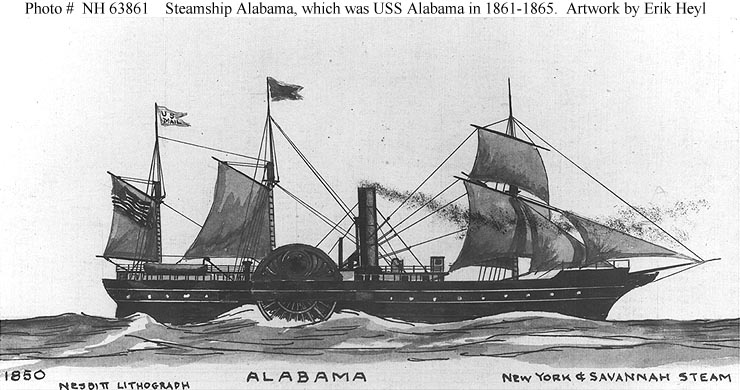

USS Alabama (1861-1865).

Previously and later the civilian steamship

Alabama (1850-1861, 1865-1878)

(Side Wheel Steamer: 1,261 tons; 1ength 214 feet 4 inches; beam 35 feet 2 inches; draft 14 feet 6 inches; speed 13 knots; complement 175; armament 8 32-pounder smooth-bore; class Alabama)

The secession of Virginia from the Union on 17 April 1861 extended Confederate territory to the southern bank of the Potomac, greatly imperiling the capital of the United States and prompting immediate action to strengthen Washington's almost nonexistent defenses with Northern troops. Two days later, supporters of the South clashed with soldiers of the 6th Massachusetts as that regiment was passing through Baltimore en route to Washington. This prompted Baltimore officials to order the destruction of railroad bridges north of their city. This action severed all direct rail connection between Washington and the large cities of the North which were sending troops to its defense. To reopen the flow of the capital, the Army commandeered a number of steamships in Northern ports for service as transports. Alabama—which would become the first ship to serve the United States Navy under the name of that state—was one of these steamers.

Laid down in 1849 by William Henry Webb in his shipyard on New York City's East River, Alabama was launched sometime in 1850, probably on either 19 January or 10 June. In any case, the steamer was delivered to the New York and Savannah Steam Navigation Co. in January 1851. Before the month was out, she sailed for Savannah on her first run for her owner.

The urgent need to strengthen the defenses of Washington ended more than a decade of commercial service along the Atlantic coast for Alabama. Taken over by the Army shortly after the Baltimore riots, the steamer embarked troops at New York and got underway for the Virginia capes in company with two other transports. Escorted by the Navy's just recommissioned brig Perry, the little convoy rounded Cape Charles and proceeded up Chesapeake Bay to the mouth of the Severn River. Upon its arrival at Annapolis on 25 April, the Union soldiers disembarked and boarded trains which, bypassing Baltimore, took them to Washington.

However, paperwork seems to have been slow in catching up with the actions taken by the Federal Government during the opening weeks of the Civil War, and the earliest charter for its use of Alabama is not dated until 10 May 1862. Meanwhile, into the summer of 1861, the steamer had continued to carry troops, munitions, and supplies to Annapolis and to Fort Monroe, the Union's only remaining hold on the shores of Virginia's strategic waters in the Virginia capes-Hampton Roads area.

The Union Navy purchased Alabama, at New York on 1 August 1861 from the firm of S. L. Mitchell and Son and, after fitting the ship out for naval service, commissioned her at the navy yard there on 30 September 1861, Comdr. Edmund Lanier in command.

The ship was assigned to Flag Officer Samuel F. Du Pont's newly established South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, which was charged with guarding the Confederate coast from the border between North and South Carolina to the tip of the Florida Peninsula. Du Pont's orders also called for him to capture some harbor within his sector as a base and a port of convenience for Union ships moving to and from the Gulf of Mexico.

While taking hold of the administrative reins of his new command, the flag officer assembled a group of warships at New York City for a joint Army-Navy expedition against Port Royal, S.C., which he had selected as the site of the new base. On 16 October, Alabama got underway in this task force and headed for the Virginia capes. Two days later, the Union men-of-war anchored in Hampton Roads, the staging point for the impending attack.

However, on the 25th, before the expedition could sortie for the South Carolina coast, word reached Du Pont that Susquehanna had suffered engine trouble which seriously impaired her efficiency. Responding to this crisis, the flag officer ordered Alabama to waters off Charleston to plug this new hole in the blockade of that strategically and symbolically important port. Thus, Alabama lost her role in the conquest of Port Royal.

When Alabama arrived on station outside Charleston bar on the 27th, she began performing more than her normal share of steaming since Flag, her companion there, was crippled by boiler trouble. On the morning of 5 November, she chased, boarded, and took possession of La Corbeta Providencia of Majorca which, four days earlier had been stopped by Monticello. While that Spanish bark's papers were on board that Union screw gunboat for examination, a storm arose and separated the two vessels. Thus, Providencia could show no papers to Comdr. Lanier, so he sent her to Hampton Roads as a prize. After the true facts were determined, the bark was turned over to the Spanish consul at New York for return to her owner.

On 12 December, while proceeding from the recently acquired Union base at Port Royal to St. Simon's Sound, Ga., Alabama sighted a large vessel some 12 to 14 miles south of Tybee Island. After a brief chase, she brought the stranger to and, on boarding, identified her as Admiral, a sailing ship which had left Liverpool two months before, bound for St. John, New Brunswick. However, the boarding party found among the ship's documents, a contract agreeing to deliver her cargo of salt, coal, and general merchandise to Savannah. Since this evidence destroyed the credibility of her clearance papers, Lanier sent Admiral to Philadelphia where she was condemned by the prize court.

During the remainder of the autumn and the ensuing winter, besides serving on blockade duty, Alabama performed widely varied duties for her squadron such as carrying dispatches and supplies to fellow warships in the area, searching for the missing schooner Peri, and towing granite-laden ships of the stone fleet to Charleston from Savannah where their use as obstructions to stop blockade runners had been obviated by hulks which the Southerners themselves had sunk in the channel leading to that port to bar the entry of Northern warships.

In late February and early March 1862, she was part of the task force which occupied Fernandia and Amelia Island, giving the Union virtual control of Florida's entire Atlantic coast. At the conclusion of this operation, Du Pont, on 6 March, ordered Alabama, to carry his chief of staff, Capt. Charles Henry Davis— who had been earmarked to head a squadron and soon would be given command of the Western Flotilla—north to deliver to the President a report of the Union's bloodless victory.

Since the Confederates had erected batteries along the Virginia bank of the Potomac making navigation of that river extremely dangerous for Union ships, the flag officer sent her to Baltimore rather than directly to Washington. His eagerness to have the good news reach the Union capital prompted Du Pont to have Alabama skip the customary stop at Hampton Roads.

This decision deprived the steamer of a front row seat at—and conceivably a role in—the most historic single naval action of the Civil War. On 9 March, as she passed between the Virginia capes and started up Chesapeake Bay, all on board could hear the guns of Monitor and Merrimack—the latter reborn as CSS Virginia—as they fought the first duel between ironclad warships. Davis later recalled the skirmish, upon his asking the master of a passing river steamer the meaning of the sound, he had been told" . . . that it was target practice . . . with the great guns on the Rip-Raps."

The ship reached Baltimore the next day, and Davis went on by train to Washington where he delivered Du Pont's report and visited the White House to give Lincoln a detailed personal account of the Florida operations. Meanwhile, Alabama began nine days in port undergoing replenishment and repairs. She stood down Chesapeake Bay on 19 March and, four days later, arrived off Port Royal and resumed duty with her squadron.

Early in April, she took station in St. Simon's Bay, Ga., and found on St. Simon's Island a recently established and growing colony of blacks who had escaped from their masters. The 26 men, 6 women, and 9 children in group were busy "... planting potatoes, corn, etc ..." but were short on food so Lanier visited a plantation on Jekyl Island and obtained a large supply of sweet potatoes to feed the former slaves until their labors bore fruit. By the time Alabama left St. Simons on the 18th, the size of the community of "contrabands" on St. Simons had increased to 89. Thus the rapid growth of this colony of former slaves illustrated the erosive effect of the war on the South's "peculiar institution" throughout the Confederacy and especially in areas controlled, or close to, Union forces.

Florida arrived in St. Simon's Bay on 18 April relieving Alabama who got underway the next morning. She joined the blockading forces off Charleston on the 20th. While on duty there on the night of 7 May, she sighted, chased, and fired at an incoming schooner which escaped in the darkness. At dawn, she sighted the elusive vessel aground off Light-House Inlet. She promptly stood in toward the stranded ship as far as the depth of water allowed and fired two rounds at the blockade runner. Both fell short. Later that morning, local people joined the schooner's crew in a race to unload this stranger's cargo before she bilged.

An even better day for Alabama began about three hours before dawn on 20 June when she assisted Keystone State in capturing Sarah as that British schooner was attempting to escape from Charleston harbor to carry 156 bales of cotton to Nassau. Alabama scored again at daybreak, when she caught Catalina after that Charleston schooner had slipped out of her home port laden with more cotton. Lanier sent that prize to Philadelphia where she was condemned by the admiralty court.

A frustrating action for Alabama, began about 90 minutes after midnight on the morning of 26 July when her sister blockader Crusader sighted, fired upon, and chased a steamer which was attempting to sneak into Charleston. The Union vessel's shells forced the blockade runner back out to sea, but Crusader's limited speed—slowed even more by ailing engines—made her no match for the fleet stranger. Alabama joined in the pursuit and followed in the stranger's wake for about 25 miles before her quarry disappeared over the horizon.

Four days later, Crusader's engines broke down completely, necessitating Alabama's towing her to Port RoyaL That mission came at a fortuitous time since Comdr. Lanier had become sick several weeks before and his condition had steadily worsened. His illness prompted Du Pont to order Lt. Comdr. James H. Gillis to relieve Lanier in command of Alabama, freeing the stricken officer to return north to recuperate. However, the assignment was brief for Gillis for, on 12 August, Lt. Comdr. William T. Truxtun took command of the ship.

During ensuing weeks, Alabama operated primarily in the shallow waters of the bays and rivers along the coast of Georgia. The highlight of her duty during this period was her capture of "... the English schooner Nellie, from Nassau, purporting to be bound for Baltimore." Truxtun sent the prize to Philadelphia for adjudication.

However, her first year of service in the Navy had taken a heavy toll on Alabama, and she needed repairs which could not be made at Port Royal. On 26 September, to return her to fighting trim, Du Pont ordered her to Philadelphia. On the voyage north, she carried "... William H. Gladding, a pilot, taken in a schooner attempting to pass the blockade at Sapelo, and reported him to you as too dangerous a man to be allowed to be adrift." The ship sailed on the 29th, reached Philadelphia on 3 October, but headed further north three days later, and arrived at Boston on the 9th and was decommissioned there on the 15th.

The steamer underwent repairs in the navy yard there for about six weeks. The exact date of her recommissioning is unknown since no logs for her between 15 October 1862 and 17 May 1864 seem to have survived. In any case, from other records, we know that Alabama—then commanded by Comdr. Edward T. Nichols—departed Boston on New Year's Day 1863, bound for the Virgin Islands to stop, or at least to gather information about, the Confederate privateer Retribution. She reached St. Thomas on the 9th where Nichols found "... much excitement among the masters of American vessels in the harbor in consequence of the appearance off the port of a Confederate privateer schooner, and the chasing by her of two American vessels back into the harbor . . . ." The next morning, Alabama got underway and cruised in the waters between St. Thomas and Puerto Rico vainly seeking the Southern raider. This cruise typified most of her subsequent operations during ensuing months in the special squadron which was established to counter the commerce destroying action of Confederate raiders and privateers. Her efforts to protect Union shipping—which were primarily devoted to catching the Southern cruisers Alabama and Florida—were ended in the summer by an outbreak of yellow fever on board. On 27 July, she was ordered to Boston in the hope that cooler weather would help to restore her crew to good health. She departed Cape Haitien, Haiti, later that day; but the growing list of deaths which occurred after she got underway and the deteriorating condition of her chief engineer and one other member of her crew forced her to put into New York where she was apparently decommissioned before transferring her entire crew to the receiving ship Magnolia. She was then towed to Portsmouth, N.H., and placed in quarantine.

Recommissioned on 17 May 1864, Acting Vol. Lt. Frank Smith in command, she stood down the Piscataqua River and headed out to sea on the 30th. After stopping at New York for 10 days, she resumed her voyage south and joined the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron at Newport News, Va., on 11 June and served in its waters through the end of the war. Highlights of her remaining year in naval service were her participation in the capture of Annie off New Inlet, N.C., as that British steamer attempted to slip out of Wilmington with a cargo of cotton, tobacco, and turpentine; and her shelling of Fort Fisher during the two attacks on that Confederate stronghold which protected Wilmington, in late-December 1864 and in mid-January 1865.

On 26 March of the latter year, she ascended the James River to City Point, Va., and remained there during the final days of Grant's drive on Richmond. After the fall of Richmond and Lee's surrender, she headed downstream on 10 April and remained in the Newport News-Hampton Roads area during the first 10 days of uncertainty, fear, and anger following Lincoln's assassination.

Alabama stood out to sea on the 24th and, two days later, entered the New York Navy Yard for repairs. Somewhat refurbished, she headed south again on 22 May and operated between Atlantic ports from Hampton Roads to the Delaware River for almost two months. She was decommissioned at Philadelphia on 14 July 1865, sold at auction there to Samuel C. Cook on 10 August 1865, and redocumented under her original name on 3 October 1865. She operated along the Atlantic coast between New York and Florida under a series of owners. In 1872 her engines were removed and on 12 September of that year she was reregistered as a schooner. The veteran ship was destroyed by fire—probably sometime in 1878—but the details of her destruction are not known.

The secession of Virginia from the Union on 17 April 1861 extended Confederate territory to the southern bank of the Potomac, greatly imperiling the capital of the United States and prompting immediate action to strengthen Washington's almost nonexistent defenses with Northern troops. Two days later, supporters of the South clashed with soldiers of the 6th Massachusetts as that regiment was passing through Baltimore en route to Washington. This prompted Baltimore officials to order the destruction of railroad bridges north of their city. This action severed all direct rail connection between Washington and the large cities of the North which were sending troops to its defense. To reopen the flow of the capital, the Army commandeered a number of steamships in Northern ports for service as transports. Alabama—which would become the first ship to serve the United States Navy under the name of that state—was one of these steamers.

Laid down in 1849 by William Henry Webb in his shipyard on New York City's East River, Alabama was launched sometime in 1850, probably on either 19 January or 10 June. In any case, the steamer was delivered to the New York and Savannah Steam Navigation Co. in January 1851. Before the month was out, she sailed for Savannah on her first run for her owner.

The urgent need to strengthen the defenses of Washington ended more than a decade of commercial service along the Atlantic coast for Alabama. Taken over by the Army shortly after the Baltimore riots, the steamer embarked troops at New York and got underway for the Virginia capes in company with two other transports. Escorted by the Navy's just recommissioned brig Perry, the little convoy rounded Cape Charles and proceeded up Chesapeake Bay to the mouth of the Severn River. Upon its arrival at Annapolis on 25 April, the Union soldiers disembarked and boarded trains which, bypassing Baltimore, took them to Washington.

However, paperwork seems to have been slow in catching up with the actions taken by the Federal Government during the opening weeks of the Civil War, and the earliest charter for its use of Alabama is not dated until 10 May 1862. Meanwhile, into the summer of 1861, the steamer had continued to carry troops, munitions, and supplies to Annapolis and to Fort Monroe, the Union's only remaining hold on the shores of Virginia's strategic waters in the Virginia capes-Hampton Roads area.

The Union Navy purchased Alabama, at New York on 1 August 1861 from the firm of S. L. Mitchell and Son and, after fitting the ship out for naval service, commissioned her at the navy yard there on 30 September 1861, Comdr. Edmund Lanier in command.

The ship was assigned to Flag Officer Samuel F. Du Pont's newly established South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, which was charged with guarding the Confederate coast from the border between North and South Carolina to the tip of the Florida Peninsula. Du Pont's orders also called for him to capture some harbor within his sector as a base and a port of convenience for Union ships moving to and from the Gulf of Mexico.

While taking hold of the administrative reins of his new command, the flag officer assembled a group of warships at New York City for a joint Army-Navy expedition against Port Royal, S.C., which he had selected as the site of the new base. On 16 October, Alabama got underway in this task force and headed for the Virginia capes. Two days later, the Union men-of-war anchored in Hampton Roads, the staging point for the impending attack.

However, on the 25th, before the expedition could sortie for the South Carolina coast, word reached Du Pont that Susquehanna had suffered engine trouble which seriously impaired her efficiency. Responding to this crisis, the flag officer ordered Alabama to waters off Charleston to plug this new hole in the blockade of that strategically and symbolically important port. Thus, Alabama lost her role in the conquest of Port Royal.

When Alabama arrived on station outside Charleston bar on the 27th, she began performing more than her normal share of steaming since Flag, her companion there, was crippled by boiler trouble. On the morning of 5 November, she chased, boarded, and took possession of La Corbeta Providencia of Majorca which, four days earlier had been stopped by Monticello. While that Spanish bark's papers were on board that Union screw gunboat for examination, a storm arose and separated the two vessels. Thus, Providencia could show no papers to Comdr. Lanier, so he sent her to Hampton Roads as a prize. After the true facts were determined, the bark was turned over to the Spanish consul at New York for return to her owner.

On 12 December, while proceeding from the recently acquired Union base at Port Royal to St. Simon's Sound, Ga., Alabama sighted a large vessel some 12 to 14 miles south of Tybee Island. After a brief chase, she brought the stranger to and, on boarding, identified her as Admiral, a sailing ship which had left Liverpool two months before, bound for St. John, New Brunswick. However, the boarding party found among the ship's documents, a contract agreeing to deliver her cargo of salt, coal, and general merchandise to Savannah. Since this evidence destroyed the credibility of her clearance papers, Lanier sent Admiral to Philadelphia where she was condemned by the prize court.

During the remainder of the autumn and the ensuing winter, besides serving on blockade duty, Alabama performed widely varied duties for her squadron such as carrying dispatches and supplies to fellow warships in the area, searching for the missing schooner Peri, and towing granite-laden ships of the stone fleet to Charleston from Savannah where their use as obstructions to stop blockade runners had been obviated by hulks which the Southerners themselves had sunk in the channel leading to that port to bar the entry of Northern warships.

In late February and early March 1862, she was part of the task force which occupied Fernandia and Amelia Island, giving the Union virtual control of Florida's entire Atlantic coast. At the conclusion of this operation, Du Pont, on 6 March, ordered Alabama, to carry his chief of staff, Capt. Charles Henry Davis— who had been earmarked to head a squadron and soon would be given command of the Western Flotilla—north to deliver to the President a report of the Union's bloodless victory.

Since the Confederates had erected batteries along the Virginia bank of the Potomac making navigation of that river extremely dangerous for Union ships, the flag officer sent her to Baltimore rather than directly to Washington. His eagerness to have the good news reach the Union capital prompted Du Pont to have Alabama skip the customary stop at Hampton Roads.

This decision deprived the steamer of a front row seat at—and conceivably a role in—the most historic single naval action of the Civil War. On 9 March, as she passed between the Virginia capes and started up Chesapeake Bay, all on board could hear the guns of Monitor and Merrimack—the latter reborn as CSS Virginia—as they fought the first duel between ironclad warships. Davis later recalled the skirmish, upon his asking the master of a passing river steamer the meaning of the sound, he had been told" . . . that it was target practice . . . with the great guns on the Rip-Raps."

The ship reached Baltimore the next day, and Davis went on by train to Washington where he delivered Du Pont's report and visited the White House to give Lincoln a detailed personal account of the Florida operations. Meanwhile, Alabama began nine days in port undergoing replenishment and repairs. She stood down Chesapeake Bay on 19 March and, four days later, arrived off Port Royal and resumed duty with her squadron.

Early in April, she took station in St. Simon's Bay, Ga., and found on St. Simon's Island a recently established and growing colony of blacks who had escaped from their masters. The 26 men, 6 women, and 9 children in group were busy "... planting potatoes, corn, etc ..." but were short on food so Lanier visited a plantation on Jekyl Island and obtained a large supply of sweet potatoes to feed the former slaves until their labors bore fruit. By the time Alabama left St. Simons on the 18th, the size of the community of "contrabands" on St. Simons had increased to 89. Thus the rapid growth of this colony of former slaves illustrated the erosive effect of the war on the South's "peculiar institution" throughout the Confederacy and especially in areas controlled, or close to, Union forces.

Florida arrived in St. Simon's Bay on 18 April relieving Alabama who got underway the next morning. She joined the blockading forces off Charleston on the 20th. While on duty there on the night of 7 May, she sighted, chased, and fired at an incoming schooner which escaped in the darkness. At dawn, she sighted the elusive vessel aground off Light-House Inlet. She promptly stood in toward the stranded ship as far as the depth of water allowed and fired two rounds at the blockade runner. Both fell short. Later that morning, local people joined the schooner's crew in a race to unload this stranger's cargo before she bilged.

An even better day for Alabama began about three hours before dawn on 20 June when she assisted Keystone State in capturing Sarah as that British schooner was attempting to escape from Charleston harbor to carry 156 bales of cotton to Nassau. Alabama scored again at daybreak, when she caught Catalina after that Charleston schooner had slipped out of her home port laden with more cotton. Lanier sent that prize to Philadelphia where she was condemned by the admiralty court.

A frustrating action for Alabama, began about 90 minutes after midnight on the morning of 26 July when her sister blockader Crusader sighted, fired upon, and chased a steamer which was attempting to sneak into Charleston. The Union vessel's shells forced the blockade runner back out to sea, but Crusader's limited speed—slowed even more by ailing engines—made her no match for the fleet stranger. Alabama joined in the pursuit and followed in the stranger's wake for about 25 miles before her quarry disappeared over the horizon.

Four days later, Crusader's engines broke down completely, necessitating Alabama's towing her to Port RoyaL That mission came at a fortuitous time since Comdr. Lanier had become sick several weeks before and his condition had steadily worsened. His illness prompted Du Pont to order Lt. Comdr. James H. Gillis to relieve Lanier in command of Alabama, freeing the stricken officer to return north to recuperate. However, the assignment was brief for Gillis for, on 12 August, Lt. Comdr. William T. Truxtun took command of the ship.

During ensuing weeks, Alabama operated primarily in the shallow waters of the bays and rivers along the coast of Georgia. The highlight of her duty during this period was her capture of "... the English schooner Nellie, from Nassau, purporting to be bound for Baltimore." Truxtun sent the prize to Philadelphia for adjudication.

However, her first year of service in the Navy had taken a heavy toll on Alabama, and she needed repairs which could not be made at Port Royal. On 26 September, to return her to fighting trim, Du Pont ordered her to Philadelphia. On the voyage north, she carried "... William H. Gladding, a pilot, taken in a schooner attempting to pass the blockade at Sapelo, and reported him to you as too dangerous a man to be allowed to be adrift." The ship sailed on the 29th, reached Philadelphia on 3 October, but headed further north three days later, and arrived at Boston on the 9th and was decommissioned there on the 15th.

The steamer underwent repairs in the navy yard there for about six weeks. The exact date of her recommissioning is unknown since no logs for her between 15 October 1862 and 17 May 1864 seem to have survived. In any case, from other records, we know that Alabama—then commanded by Comdr. Edward T. Nichols—departed Boston on New Year's Day 1863, bound for the Virgin Islands to stop, or at least to gather information about, the Confederate privateer Retribution. She reached St. Thomas on the 9th where Nichols found "... much excitement among the masters of American vessels in the harbor in consequence of the appearance off the port of a Confederate privateer schooner, and the chasing by her of two American vessels back into the harbor . . . ." The next morning, Alabama got underway and cruised in the waters between St. Thomas and Puerto Rico vainly seeking the Southern raider. This cruise typified most of her subsequent operations during ensuing months in the special squadron which was established to counter the commerce destroying action of Confederate raiders and privateers. Her efforts to protect Union shipping—which were primarily devoted to catching the Southern cruisers Alabama and Florida—were ended in the summer by an outbreak of yellow fever on board. On 27 July, she was ordered to Boston in the hope that cooler weather would help to restore her crew to good health. She departed Cape Haitien, Haiti, later that day; but the growing list of deaths which occurred after she got underway and the deteriorating condition of her chief engineer and one other member of her crew forced her to put into New York where she was apparently decommissioned before transferring her entire crew to the receiving ship Magnolia. She was then towed to Portsmouth, N.H., and placed in quarantine.

Recommissioned on 17 May 1864, Acting Vol. Lt. Frank Smith in command, she stood down the Piscataqua River and headed out to sea on the 30th. After stopping at New York for 10 days, she resumed her voyage south and joined the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron at Newport News, Va., on 11 June and served in its waters through the end of the war. Highlights of her remaining year in naval service were her participation in the capture of Annie off New Inlet, N.C., as that British steamer attempted to slip out of Wilmington with a cargo of cotton, tobacco, and turpentine; and her shelling of Fort Fisher during the two attacks on that Confederate stronghold which protected Wilmington, in late-December 1864 and in mid-January 1865.

On 26 March of the latter year, she ascended the James River to City Point, Va., and remained there during the final days of Grant's drive on Richmond. After the fall of Richmond and Lee's surrender, she headed downstream on 10 April and remained in the Newport News-Hampton Roads area during the first 10 days of uncertainty, fear, and anger following Lincoln's assassination.

Alabama stood out to sea on the 24th and, two days later, entered the New York Navy Yard for repairs. Somewhat refurbished, she headed south again on 22 May and operated between Atlantic ports from Hampton Roads to the Delaware River for almost two months. She was decommissioned at Philadelphia on 14 July 1865, sold at auction there to Samuel C. Cook on 10 August 1865, and redocumented under her original name on 3 October 1865. She operated along the Atlantic coast between New York and Florida under a series of owners. In 1872 her engines were removed and on 12 September of that year she was reregistered as a schooner. The veteran ship was destroyed by fire—probably sometime in 1878—but the details of her destruction are not known.

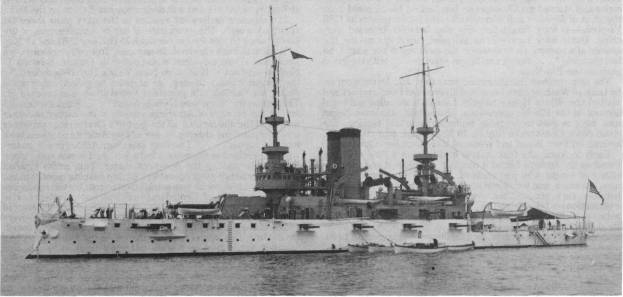

USS Alabama (Battleship # 8)

(later BB-8), 1900-1921

Summary

Battleship No. 8:

Displacement 11,565 (normal load);

Length 374 feet 10 inches; beam 72 feet 5 inches;

Draft 25 feet (f.) (aft);

Speed 16 knots; complement 536;

Armament 4 13-inch guns, 14 6-inch guns, 16 6-pounders, 4 1-pounders, 4 .30-cal. mg., 4 18-inch torpedo tubes;

Class Illinois)

The second Alabama (Battleship No. 8) was laid down on 1 December 1896 at Philadelphia, Pa., by the William Cramp and Sons Ship and Engine Building Co.; launched on 18 May 1898; sponsored by Miss Mary Morgan, daughter of the Honorable John T. Morgan, United States Senator from Georgia; and commissioned on 16 October 1900, Capt. Willard H. Brownson in command.

Though assigned to the North Atlantic Station, Alabama did not begin operations with that unit until early the following year. The warship remained at Philadelphia until 13 December when she got underway for the brief trip to New York. She stayed at New York through the New Year and until the latter part of January 1901. Finally, on 27 January, the battleship headed south for winter exercises with the Fleet at the drill grounds in the Gulf of Mexico near Pensacola, Fla. Alabama's Navy career began in earnest with her arrival in the gulf early in February. With a single exception in 1904, each year from 1901 to 1907, she conducted Fleet exercises and gunnery drills in the Gulf of Mexico and the West Indies in the wintertime before returning north for repairs and operations off the northeastern coast during the summer and autumn. The exception came in the spring of 1904 after the conclusion of winter maneuvers when she departed Pensacola in company with Kearsarge (Battleship No. 5), Maine (Battleship No. 10), Iowa (Battleship No. 4), Olympia (Cruiser No. 6), Baltimore (Cruiser No. 3), and Cleveland (Cruiser No. 19) on a voyage to Portugal and the Mediterranean. After a ceremonial visit to Lisbon honoring the entrance of the Infante into the Portuguese naval school, Alabama and the other three battleships cruised the Mediterranean until mid-August. Returning by way of the Azores, she and her traveling companions arrived in Newport, R.I., on 29 August. Late in September, the warship entered the League Island Navy Yard for repairs. Early in December, Alabama left the yard and resumed cruising with the North Atlantic Fleet.

Near the end of 1907, the battleship set out upon a special mission. On 16 December 1907, she stood out of Hampton Roads in company with what became known as the Great White Fleet. Alabama accompanied the Fleet on its voyage around the South American continent as far as San Francisco. On 18 May 1908 when the bulk of the Fleet headed north to visit the Pacific northwest, she remained at San Francisco for repairs at the Mare Island Navy Yard. As a consequence, the warship did not participate in the celebrated visit to Japan. Instead, Alabama and Maine departed San Francisco on 8 June to complete their own, more direct, circumnavigation of the globe. Steaming by way of Honolulu and Guam, the two battleships arrived at Manila in the Philippines on 20 July. In August, they visited Singapore and Colombo on the island of Ceylon. From Colombo, the two battleships made their way, via Aden on the Arabian Peninsula,to the Suez Canal. Through the canal early in September, Alabama and Maine made an expeditious transit of the Mediterranean Sea, pausing only at Naples at mid-month. Following a port call at Gibraltar, they embarked upon the Atlantic passage on 4 October. They made one stop, in the Azores, on their way across the Atlantic. On 19 October as they neared the end of their long voyage, the two battleships parted company. Maine headed for Portsmouth, N.H.; and Alabama steered for New York. Both reached their destinations on the 20th

Though assigned to the North Atlantic Station, Alabama did not begin operations with that unit until early the following year. The warship remained at Philadelphia until 13 December when she got underway for the brief trip to New York. She stayed at New York through the New Year and until the latter part of January 1901. Finally, on 27 January, the battleship headed south for winter exercises with the Fleet at the drill grounds in the Gulf of Mexico near Pensacola, Fla. Alabama's Navy career began in earnest with her arrival in the gulf early in February. With a single exception in 1904, each year from 1901 to 1907, she conducted Fleet exercises and gunnery drills in the Gulf of Mexico and the West Indies in the wintertime before returning north for repairs and operations off the northeastern coast during the summer and autumn. The exception came in the spring of 1904 after the conclusion of winter maneuvers when she departed Pensacola in company with Kearsarge (Battleship No. 5), Maine (Battleship No. 10), Iowa (Battleship No. 4), Olympia (Cruiser No. 6), Baltimore (Cruiser No. 3), and Cleveland (Cruiser No. 19) on a voyage to Portugal and the Mediterranean. After a ceremonial visit to Lisbon honoring the entrance of the Infante into the Portuguese naval school, Alabama and the other three battleships cruised the Mediterranean until mid-August. Returning by way of the Azores, she and her traveling companions arrived in Newport, R.I., on 29 August. Late in September, the warship entered the League Island Navy Yard for repairs. Early in December, Alabama left the yard and resumed cruising with the North Atlantic Fleet.

Near the end of 1907, the battleship set out upon a special mission. On 16 December 1907, she stood out of Hampton Roads in company with what became known as the Great White Fleet. Alabama accompanied the Fleet on its voyage around the South American continent as far as San Francisco. On 18 May 1908 when the bulk of the Fleet headed north to visit the Pacific northwest, she remained at San Francisco for repairs at the Mare Island Navy Yard. As a consequence, the warship did not participate in the celebrated visit to Japan. Instead, Alabama and Maine departed San Francisco on 8 June to complete their own, more direct, circumnavigation of the globe. Steaming by way of Honolulu and Guam, the two battleships arrived at Manila in the Philippines on 20 July. In August, they visited Singapore and Colombo on the island of Ceylon. From Colombo, the two battleships made their way, via Aden on the Arabian Peninsula,to the Suez Canal. Through the canal early in September, Alabama and Maine made an expeditious transit of the Mediterranean Sea, pausing only at Naples at mid-month. Following a port call at Gibraltar, they embarked upon the Atlantic passage on 4 October. They made one stop, in the Azores, on their way across the Atlantic. On 19 October as they neared the end of their long voyage, the two battleships parted company. Maine headed for Portsmouth, N.H.; and Alabama steered for New York. Both reached their destinations on the 20th

Alabama was placed in reserve at New York on 3 November 1908. Though she remained inactive at New York, the battleship was not decommissioned until 17 August 1909. The warship underwent an extensive overhaul that lasted until the early part of 1912. On 17 April 1912, she was placed in commission, second reserve, at New York, Comdr. Charles F. Preston in command. At that point, she became an element of the newly established Atlantic Reserve Fleet. According to that concept, the Navy organized a unit that comprised nine of the older battleships as well as Brooklyn (Armored Cruiser No. 3), Columbia (Cruiser No. 12), and Minneapolis (Cruiser No. 13) for the purpose of keeping those ships constantly ready for active service using the fiscal expedient of severely reduced complements that could be filled out rapidly by naval militiamen and volunteers in an emergency. The unit as a whole possessed enough officers and men to take two or three of the ships to sea on a rotating basis to test their material readiness and to exercise the sailors at drill.

Alabama was placed in full commission on 25 July 1912 and operated with the Atlantic Fleet off the New England coast through the summer. She was returned to reserve status—in commission, first reserve—at New York on 10 September 1912. Late in the spring of 1913, the Navy added a new dimension to the concept of the Atlantic Reserve Fleet by having the warships of that unit embark detachments of the various state naval militias for training afloat in a manner similar in many respects to the contemporary Navy's selected reserve program. During the summer of 1913, Alabama cruised along the east coast and made two round-trip voyages to Bermuda to train naval militiamen from Maryland, the District of Columbia, New York, Rhode Island, Maine, North Carolina, and Indiana. She ended her last training cruise of the year at Philadelphia on 2 September. The battleship was placed in ordinary on 31 October 1913 and in reserve on 1 July 1914.

Though still in commission, she passed the next 30 months in relative inactivity with the Reserve Force, Atlantic Fleet, at Philadelphia. America's shift toward belligerency in World War I, however, brought Alabama out of the doldrums of the peacetime reserve at the beginning of 1917. On 22 January, she became receiving ship at Philadelphia, embarking drafts of recruits for training. In mid-March, the battleship moved south to the lower reaches of the Chesapeake Bay and began transforming landsmen into sailors. She took a brief respite from her rigorous training schedule on 6 April 1917 for the announcement of the United States' declaration of war on the Central Powers. Two days later, Alabama became flagship of Division 1, Atlantic Fleet. For the remainder of World War I, the warship conducted recruit training missions in the lower Chesapeake Bay and in the coastal waters of the Atlantic seaboard, though she made one visit to the Gulf of Mexico in late June and early July of 1918.

Alabama was placed in full commission on 25 July 1912 and operated with the Atlantic Fleet off the New England coast through the summer. She was returned to reserve status—in commission, first reserve—at New York on 10 September 1912. Late in the spring of 1913, the Navy added a new dimension to the concept of the Atlantic Reserve Fleet by having the warships of that unit embark detachments of the various state naval militias for training afloat in a manner similar in many respects to the contemporary Navy's selected reserve program. During the summer of 1913, Alabama cruised along the east coast and made two round-trip voyages to Bermuda to train naval militiamen from Maryland, the District of Columbia, New York, Rhode Island, Maine, North Carolina, and Indiana. She ended her last training cruise of the year at Philadelphia on 2 September. The battleship was placed in ordinary on 31 October 1913 and in reserve on 1 July 1914.

Though still in commission, she passed the next 30 months in relative inactivity with the Reserve Force, Atlantic Fleet, at Philadelphia. America's shift toward belligerency in World War I, however, brought Alabama out of the doldrums of the peacetime reserve at the beginning of 1917. On 22 January, she became receiving ship at Philadelphia, embarking drafts of recruits for training. In mid-March, the battleship moved south to the lower reaches of the Chesapeake Bay and began transforming landsmen into sailors. She took a brief respite from her rigorous training schedule on 6 April 1917 for the announcement of the United States' declaration of war on the Central Powers. Two days later, Alabama became flagship of Division 1, Atlantic Fleet. For the remainder of World War I, the warship conducted recruit training missions in the lower Chesapeake Bay and in the coastal waters of the Atlantic seaboard, though she made one visit to the Gulf of Mexico in late June and early July of 1918.

After the armistice on 11 November 1918, her recruit training duties continued but began to diminish somewhat in intensity. During February and March of 1919, the battleship steamed south to the West Indies for winter maneuvers. She returned to Philadelphia in mid-April for routine repairs before heading for Annapolis to embark Naval Academy midshipmen for their summer training cruise. On 28 and 29 May, Alabama made the short trip from Philadelphia to Annapolis. She left Annapolis on 9 June with 184 midshipmen embarked. During the first part of the cruise, Alabama visited the West Indies and made a trip through the Panama Canal and back. In midJuly, she voyaged to New York and the New England coast. August saw her return south for maneuvers at the drill grounds. Alabama disembarked the midshipmen at Annapolis at the end of August and returned to Philadelphia.

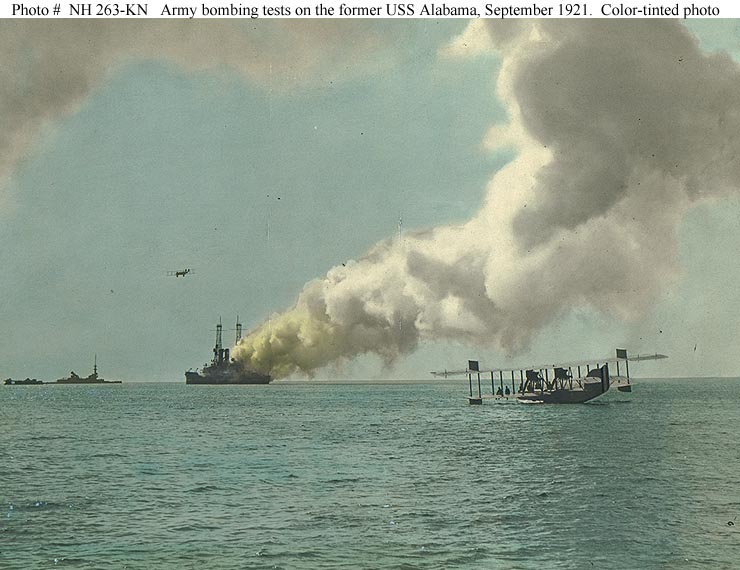

After more than nine months at Philadelphia lingering in a sort of naval purgatory, the battleship was finally decommissioned on 7 May 1920. On 15 September 1921, Alabatna was transferred to the War Department to be used as a target, and her name was struck from the Navy list. Subjected to aerial bombing tests in Chesapeake Bay by planes of the Army Air Service, the former warship sank in shallow water on 27 September 1921. On 19 March 1924, her sunken hulk was sold for scrap.

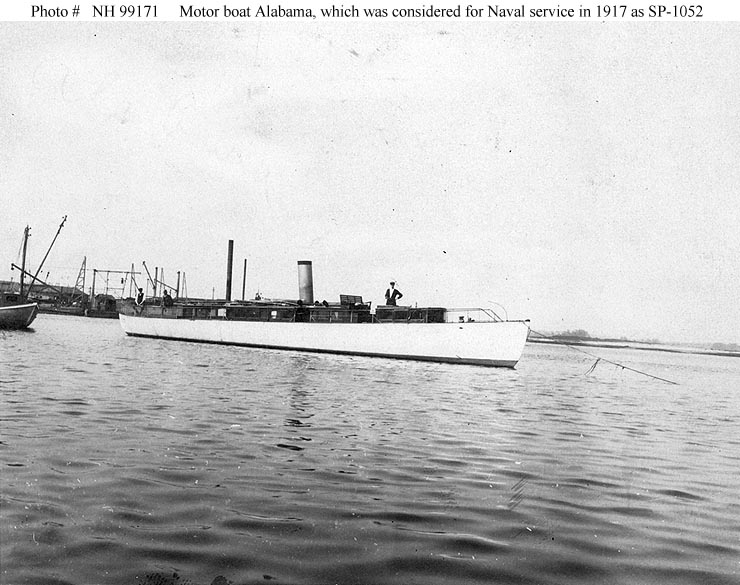

USS Alabama (SP-1052)

1906-1917??

Summary

Builder: George Lawley and Sons, South Boston, MA

Launched: 1906

Type: motor boat

Length: 69 ft (21 m)

Alabama was a 69-foot motor boat built in 1906 at South Boston, MA, by George Lawley and Sons. She was inspected by the Navy in the summer of 1917. Records indicate that on 25 July 1917 the Navy concluded an agreement with her owners, the American and British Manufacturing Co., Bridgeport, CT, for possible future acquisition of the boat. By the terms of that agreement, Alabama — assigned the designation SP-1052 —- was "enrolled in the Naval Coast Defense Reserve." All indications are, however, that Alabama never saw actual naval service, possibly remaining "enrolled" in a reserve capacity, since she does not appear on contemporary lists of commandeered, chartered, or leased small craft actually used by the Navy during World War I.

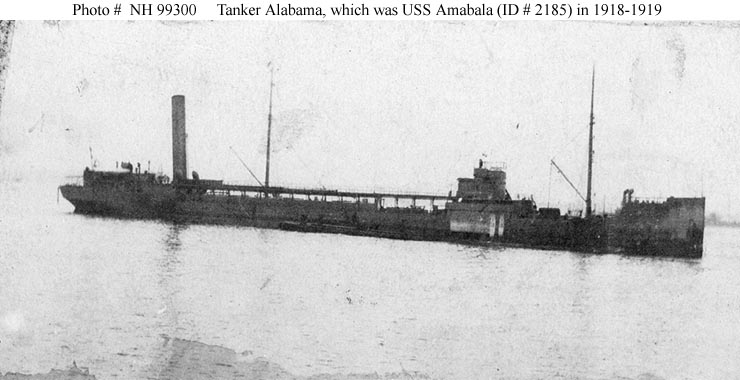

Alabama (American Tanker, 1901).

Originally named Northtown.

Served as USS Amabala (ID # 2185) in 1918-1919

Northtown, a 2621 gross ton tanker, was built at South Chicago, Illinois, for commercial employment. She operated on the Great Lakes until 1907, then shifted her base to Port Arthur, Texas. The ship was rebuilt in 1914 and renamed Alabama at about that time. The Navy took her over in August 1918 and placed her in commission as USS Amabala (ID # 2185), a rather curious renaming made to avoid confusion with the battleship Alabama.

Assigned to the Naval Overseas Transportation Service, Amabala steamed across the Atlantic in September 1918 to begin the important work of supplying fuel oil to U.S. warships based at Berehaven, Ireland. She continued in this duty until after the November Armistice ended active combat operations. At the beginning of December the tanker moved to Brest, France, where she fueled American ships until mid-month. Amabala then returned to the United States, arriving in early January 1919. She was decommissioned in late February and given back to her owner.

Her name changed back to Alabama, she had a long subsequent commercial career, under the U.S. flag until 1946-1947 and thereafter under Venezuelan registry. The old tanker appears to have been removed from service in the early 1950s.

Assigned to the Naval Overseas Transportation Service, Amabala steamed across the Atlantic in September 1918 to begin the important work of supplying fuel oil to U.S. warships based at Berehaven, Ireland. She continued in this duty until after the November Armistice ended active combat operations. At the beginning of December the tanker moved to Brest, France, where she fueled American ships until mid-month. Amabala then returned to the United States, arriving in early January 1919. She was decommissioned in late February and given back to her owner.

Her name changed back to Alabama, she had a long subsequent commercial career, under the U.S. flag until 1946-1947 and thereafter under Venezuelan registry. The old tanker appears to have been removed from service in the early 1950s.

USS Alabama (BB-60), 1942-1964

SUMMARY

BB-60:

Displacement 35,000;

Length 680 feet;

Beam 108 feet 2 inches;

Draft 36 feet 2 inches;

Speed 27.5 knots;

Complement 1,793;

Armament 9 16-inch guns, 20 5-inch guns; 24 40 millimeter, 22 20 millimeter;

Cass South Dakota)

BB-60:

Displacement 35,000;

Length 680 feet;

Beam 108 feet 2 inches;

Draft 36 feet 2 inches;

Speed 27.5 knots;

Complement 1,793;

Armament 9 16-inch guns, 20 5-inch guns; 24 40 millimeter, 22 20 millimeter;

Cass South Dakota)

Launch of the USS Alabama on February 16, 1942 from Archives.org.

The third Alabama (BB-60) was laid down on 1 February 1940 by the Norfolk (Virginia.) Navy Yard; launched on 16 February 1942; sponsored by Mrs. Lister Hill, wife of the senior Senator from Alabama; and commissioned on 16 August 1942, Capt. George B. Wilson in command.

After fitting out, Alabama commenced her shakedown cruise in Chesapeake Bay on Armistice Day (11 November) 1942. As the year 1943 began, the new battleship headed north to conduct operational training out of Casco Bay, Maine. She returned to Chesapeake Bay on 11 January 1943 to carry out the last week of shakedown training. Following a period of availability and logistics support at Norfolk, Alabama was assigned to Task Group (TG) 22.2, and returned to Casco Bay for tactical maneuvers on 13 February 1943.

With the movement of substantial British strength toward the Mediterranean theater, to prepare for the invasion of Sicily, the Royal Navy lacked the heavy ships necessary to cover the northern convoy routes. The British appeal for help on those lines soon led to the temporary assignment of Alabama and South Dakota (BB-57) to the Home Fleet.

On 2 April 1943, Alabama--as part of Task Force (TF) 22— sailed for the Orkney Islands with her sister ship and a screen of five destroyers. Proceeding via Little Placentia Sound, Argentia, Newfoundland, the battleship reached Scapa Flow on 19 May 1943, reporting for duty with TF 61 and becoming a unit of the British Home Fleet. She soon embarked on a period of intensive operational training to coordinate joint operations.

After fitting out, Alabama commenced her shakedown cruise in Chesapeake Bay on Armistice Day (11 November) 1942. As the year 1943 began, the new battleship headed north to conduct operational training out of Casco Bay, Maine. She returned to Chesapeake Bay on 11 January 1943 to carry out the last week of shakedown training. Following a period of availability and logistics support at Norfolk, Alabama was assigned to Task Group (TG) 22.2, and returned to Casco Bay for tactical maneuvers on 13 February 1943.

With the movement of substantial British strength toward the Mediterranean theater, to prepare for the invasion of Sicily, the Royal Navy lacked the heavy ships necessary to cover the northern convoy routes. The British appeal for help on those lines soon led to the temporary assignment of Alabama and South Dakota (BB-57) to the Home Fleet.

On 2 April 1943, Alabama--as part of Task Force (TF) 22— sailed for the Orkney Islands with her sister ship and a screen of five destroyers. Proceeding via Little Placentia Sound, Argentia, Newfoundland, the battleship reached Scapa Flow on 19 May 1943, reporting for duty with TF 61 and becoming a unit of the British Home Fleet. She soon embarked on a period of intensive operational training to coordinate joint operations.

Early in June, Alabama and her sister ship, along with British Home Fleet units, covered the reinforcement of the garrison on the island of Spitzbergen, which lay on the northern flank of the convoy route to Russia, in an operation that took the ship across the Arctic Circle. Soon after her return to Scapa Flow, she was inspected by Admiral Harold R. Stark, Commander, United States Naval Forces, Europe.

Shortly thereafter, in July, Alabama participated in Operation "Governor," a diversion aimed toward southern Norway, to draw German attention away from the real Allied thrust, toward Sicily. It had also been devised to attempt to lure out the German battleship Tirpitz, the sister ship of the famed, but shortlived, Bismarck, but the Germans did not rise to the challenge, and the enemy battleship remained in her Norwegian lair.

Alabama was detached from the British Home Fleet on 1 August 1943, and, in company with South Dakota and screening destroyers, sailed for Norfolk, arriving there on 9 August. For the next ten days, Alabama underwent a period of overhaul and repairs. This work completed, the battleship departed Norfolk on 20 August 1943 for the Pacific. Transiting the Panama Canal five days later, she dropped anchor in Havannah Harbor, at Efate, in the New Hebrides, on 14 September.

Following a month and a half of exercises and training, with fast carrier task groups, the battleship moved to Fiji on 7 November. Alabama sailed on 11 November to take part in Operation "Galvanic", the assault on the Japanese-held Gilbert Islands. She screened the fast carriers as they launched attacks on Jaluit and Mille atolls, Marshall Islands, to neutralize Japanese airfields located there. Alabama supported landings on Tarawa on 20 November and later took part in the securing of Betio and Makin. On the night of 26 November, Alabama twice opened fire to drive off enemy aircraft that approached her formation.

On 8 December 1943, Alabama, along with five other fast battleships, carried out the first Pacific gunfire strike conducted by that type of warship. Alabama's guns hurled 535 rounds into enemy strongpoints, as she and her sister ships bombarded Nauru Island, an enemy phosphate-producing center, causing severe damage to shore installations there. She also took the destroyer Boyd (DD-544), alongside after that ship had received a direct hit from a Japanese shore battery on Nauru, and brought three injured men on board for treatment.

She then escorted the carriers Blinker Hill (CV-17) and Monterey (CVL-26) back to Efate, arriving on 12 December. Alabama departed the New Hebrides for Pearl Harbor on 5 January 1944, arrived on the 12th, and underwent a brief drydocking at the Pearl Harbor Navy Yard. After replacement of her port outboard propeller, and routine maintenance, Alabama was again underway to return to action in the Pacific.

Alabama reached Funafuti, Ellice Islands, on 21 January 1944, and there rejoined the fleet. Assigned to Task Group (TG) 58.2, which was formed around Essex (CV-9), Alabama left the Ellice Islands on 25 January to help carry out Operation "Flintlock," the invasion of the Marshall Islands. Alabama, along with sister ship South Dakota and the fast battleship North Carolina (BB-55), bombarded Roi on 29 January and Namur on 30 January; she hurled 330 rounds of 16-inch and 1,562 of 5-inch toward Japanese targets, destroying planes, airfield facilities, blockhouses, buildings, and gun emplacements. Over the following days of the campaign, Alabama patroled the area north of Kwajalein Atoll. On 12 February 1944, Alabama sortied with the Bunker Hill task group to launch attacks on Japanese installations, aircraft and shipping at Truk. Those raids, launched on 16 and 17 February, caused heavy damage to enemy shipping concentrated at that island base.

Leaving Truk, Alabama began steaming toward the Marianas to assist in strikes on Tinian, Saipan and Guam. During this action, while repelling enemy air attacks on 21 February 1944, 5-inch mount no. 9 accidentally fired into mount no. 5. Five men died, and 11 were wounded in the mishap.

After the strikes were completed on 22 February, Alabama conducted a sweep looking for crippled enemy ships southeast of Saipan, and eventually returned to Majuro on 26 February 1944. There she served temporarily as flagship for Vice Admiral Marc A. Mitscher, Commander, TF 58, from 3 to 8 March.

Alabama's next mission was to screen the fast carriers as they hurled air strikes against Japanese positions on Palau, Yap, Ulithi, and Woleai, Caroline Islands. She steamed from Majuro on 22 March 1944 with TF 58 in the screen of Yorkiown (CV-10). On the night of 29 March, about six enemy planes approached TG 58.3, in which Alabama was operating, and four broke off to attack ships in the vicinity of the battleship. Alabama downed one unassisted, and helped in the destruction of another.

On 30 March, planes from TF 58 began bombing Japanese airfields, shipping, fleet servicing facilities, and other installations on the islands of Palau, Yap, Ulithi and Woleai. During that day, Alabama again provided antiaircraft fire whenever enemy planes appeared. At 2045 on the 30th, a single plane approached TG 58.3, but Alabama and other ships drove it off before it could cause any damage.

The battleship returned briefly to Majuro, before she sailed on 13 April with TF 58, this time in the screen of Enterprise (CV-6). In the next three weeks, TF 58 hit enemy targets on Hollandia, Wakde, Sawar, and Sarmi along the New Guinea coast; covered Army landings at Aitape, Tanahmerah Bay, and Humboldt Bay; and conducted further strikes on Truk.

As part of the preliminaries to the invasion of the Marianas, Alabama, in company with five other fast battleships, shelled the large island of Ponape, in the Carolines, the site of a Japanese airfield and seaplane base. As Alabama's Capt. Fred T. Kirtland subsequently noted, the bombardment, of 70 minutes' duration, was conducted in a "leisurely manner." Alabama then returned to Majuro on 4 May 1944 to prepare for the invasion of the Marianas.

Shortly thereafter, in July, Alabama participated in Operation "Governor," a diversion aimed toward southern Norway, to draw German attention away from the real Allied thrust, toward Sicily. It had also been devised to attempt to lure out the German battleship Tirpitz, the sister ship of the famed, but shortlived, Bismarck, but the Germans did not rise to the challenge, and the enemy battleship remained in her Norwegian lair.

Alabama was detached from the British Home Fleet on 1 August 1943, and, in company with South Dakota and screening destroyers, sailed for Norfolk, arriving there on 9 August. For the next ten days, Alabama underwent a period of overhaul and repairs. This work completed, the battleship departed Norfolk on 20 August 1943 for the Pacific. Transiting the Panama Canal five days later, she dropped anchor in Havannah Harbor, at Efate, in the New Hebrides, on 14 September.

Following a month and a half of exercises and training, with fast carrier task groups, the battleship moved to Fiji on 7 November. Alabama sailed on 11 November to take part in Operation "Galvanic", the assault on the Japanese-held Gilbert Islands. She screened the fast carriers as they launched attacks on Jaluit and Mille atolls, Marshall Islands, to neutralize Japanese airfields located there. Alabama supported landings on Tarawa on 20 November and later took part in the securing of Betio and Makin. On the night of 26 November, Alabama twice opened fire to drive off enemy aircraft that approached her formation.

On 8 December 1943, Alabama, along with five other fast battleships, carried out the first Pacific gunfire strike conducted by that type of warship. Alabama's guns hurled 535 rounds into enemy strongpoints, as she and her sister ships bombarded Nauru Island, an enemy phosphate-producing center, causing severe damage to shore installations there. She also took the destroyer Boyd (DD-544), alongside after that ship had received a direct hit from a Japanese shore battery on Nauru, and brought three injured men on board for treatment.

She then escorted the carriers Blinker Hill (CV-17) and Monterey (CVL-26) back to Efate, arriving on 12 December. Alabama departed the New Hebrides for Pearl Harbor on 5 January 1944, arrived on the 12th, and underwent a brief drydocking at the Pearl Harbor Navy Yard. After replacement of her port outboard propeller, and routine maintenance, Alabama was again underway to return to action in the Pacific.

Alabama reached Funafuti, Ellice Islands, on 21 January 1944, and there rejoined the fleet. Assigned to Task Group (TG) 58.2, which was formed around Essex (CV-9), Alabama left the Ellice Islands on 25 January to help carry out Operation "Flintlock," the invasion of the Marshall Islands. Alabama, along with sister ship South Dakota and the fast battleship North Carolina (BB-55), bombarded Roi on 29 January and Namur on 30 January; she hurled 330 rounds of 16-inch and 1,562 of 5-inch toward Japanese targets, destroying planes, airfield facilities, blockhouses, buildings, and gun emplacements. Over the following days of the campaign, Alabama patroled the area north of Kwajalein Atoll. On 12 February 1944, Alabama sortied with the Bunker Hill task group to launch attacks on Japanese installations, aircraft and shipping at Truk. Those raids, launched on 16 and 17 February, caused heavy damage to enemy shipping concentrated at that island base.

Leaving Truk, Alabama began steaming toward the Marianas to assist in strikes on Tinian, Saipan and Guam. During this action, while repelling enemy air attacks on 21 February 1944, 5-inch mount no. 9 accidentally fired into mount no. 5. Five men died, and 11 were wounded in the mishap.

After the strikes were completed on 22 February, Alabama conducted a sweep looking for crippled enemy ships southeast of Saipan, and eventually returned to Majuro on 26 February 1944. There she served temporarily as flagship for Vice Admiral Marc A. Mitscher, Commander, TF 58, from 3 to 8 March.

Alabama's next mission was to screen the fast carriers as they hurled air strikes against Japanese positions on Palau, Yap, Ulithi, and Woleai, Caroline Islands. She steamed from Majuro on 22 March 1944 with TF 58 in the screen of Yorkiown (CV-10). On the night of 29 March, about six enemy planes approached TG 58.3, in which Alabama was operating, and four broke off to attack ships in the vicinity of the battleship. Alabama downed one unassisted, and helped in the destruction of another.

On 30 March, planes from TF 58 began bombing Japanese airfields, shipping, fleet servicing facilities, and other installations on the islands of Palau, Yap, Ulithi and Woleai. During that day, Alabama again provided antiaircraft fire whenever enemy planes appeared. At 2045 on the 30th, a single plane approached TG 58.3, but Alabama and other ships drove it off before it could cause any damage.

The battleship returned briefly to Majuro, before she sailed on 13 April with TF 58, this time in the screen of Enterprise (CV-6). In the next three weeks, TF 58 hit enemy targets on Hollandia, Wakde, Sawar, and Sarmi along the New Guinea coast; covered Army landings at Aitape, Tanahmerah Bay, and Humboldt Bay; and conducted further strikes on Truk.

As part of the preliminaries to the invasion of the Marianas, Alabama, in company with five other fast battleships, shelled the large island of Ponape, in the Carolines, the site of a Japanese airfield and seaplane base. As Alabama's Capt. Fred T. Kirtland subsequently noted, the bombardment, of 70 minutes' duration, was conducted in a "leisurely manner." Alabama then returned to Majuro on 4 May 1944 to prepare for the invasion of the Marianas.

After a month spent in exercises and refitting, Alabama again got under way with TF 58 to participate in Operation "Forager." On 12 June, Alabama screened the carriers striking Saipan. On 13 June, Alabama took part in a six-hour preinvasion bombardment of the west coast of Saipan, to soften the defenses and cover the initial minesweeping operations. Her spotting planes reported that her salvoes had caused great destruction and fires in Garapan town. Though the shelling appeared successful, it proved a failure due to the lack of specialized training and experience required for successful shore bombardent. Strikes continued as troops invaded Saipan on 15 June.

On 19 June, during the Battle of the Philippine Sea, Alabama operated with TG 58.7, and provided the first warning to TF 58 of the incoming Japanese air strike when she reported having detected a large bogie “bearing 268º true, distance 141 miles, angels 24 or greater, closing…” on her air search radar at 1006. In response to Commander Task Force 58 (Vice Admiral Marc A. Mitscher)’s immediate request for confirmation: battleship Iowa (BB-61) substantiated Alabama’s report.

Beginning at 1046 and continuing over the course of the next five hours, the Japanese hurled repeated strikes against Vice Admiral Mitscher’s fast carrier force, seven raids in all. Three of those involved TG 58.7, and two of which saw Alabama opening fire.

In the first instance, only two planes managed to penetrate the formation to attack South Dakota, but her sister ship suffered one bomb hit that killed one officer and 20 enlisted men and wounded an additional 23. An hour later a second wave, composed largely of torpedo bombers, bore in, but Alabama’s barrage discouraged two planes from attacking the already bloodied South Dakota. The intense concentration paid to the incoming torpedo planes left one dive bomber nearly undetected, and it managed to drop its load near Alabama; the two small bombs were near-misses, and caused no damage.

What U.S. Navy pilots came to call the “Marianas Turkey Shoot" severely depleted Japanese naval air power, and Alabama had had a hand in it, as Commander TG 58.7 (Vice Admiral Willis A. Lee) recognized in his TBS (low-frequency voice radio) message at 1247: “In the matter of reporting initial bogies, to IOWA well done, to ALABAMA very well done.” Alabama’s “early warning” had allowed the carriers to scramble their fighters and intercept the in-bound enemy “at a considerable distance” from TF 58 than would otherwise have been possible.

Alabama continued patrolling areas around the Marianas to protect the American landing forces on Saipan, screening the fast carriers as they struck enemy shipping, aircraft, and shore installations on Guam, Tinian, Rota, and Saipan. She then retired to the Marshalls for upkeep.

Alabama—as flagship for Rear Admiral E. W. Hanson, Commander, Battleship Division 9—left Eniwetok on 14 July 1944, sailing with the task group formed around Bunker Hill. She screened the fast carriers as they conducted preinvasion attacks and support of the landings on the island of Guam on 21 July. She returned briefly to Eniwetok on 11 August. On 30 August she got underway in the screen of Essex_ to carry out Operation "Stalemate II," the seizure of Palau, Ulithi, and Yap. On 6 through 8 September, the forces launched strikes on the Carolines.

Alabama departed the Carolines to sail to the Philippines and provided cover for the carriers striking the islands of Cebu, Leyte, Bohol, and Negros from 12 to 14 September. The carriers launched strikes on snipping and installations in the Manila Bay area on 21 and 22 September, and in the central Philippines area on 24 September. Alabama retired briefly to Saipan on 28 September, then proceeded to Ulithi on 1 October 1944.

On 6 October 1944, Alabama sailed with TF 38 to support the liberation of the Philippines. Again operating as part of a fast carrier task group, Alabama protected the flattops while they launched strikes on Japanese facilities at Okinawa, in the Pescadores, and Formosa.

Detached from the Formosa area on 14 October to sail toward Luzon, the fast battleship again used her antiaircraft batteries in support of the carriers as enemy aircraft attempted to attack the formation. Alabama's gunners claimed three enemy aircraft shot down and a fourth damaged. By 15 October, Alabama was supporting landing operations on Leyte. She then screened the carriers as they conducted air strikes on Cebu, Negros, Panay, northern Mindanao, and Leyte on 21 October 1944.

Alabama, as part of the Enterprise screen, supported air operations against the Japanese Southern Force in the area off Surigao Strait, then moved north to strike the powerful Japanese Central Force heading for San Bernardino Strait. After receiving reports of a third Japanese force, the battleship served in the screen of the fast carrier task force as it sped to Cape Engano. On 24 October, although American air strikes destroyed four Japanese carriers in the Battle off Cape Engano, the Japanese Central Force under Admiral Kurita had transited San Bernardino Strait and emerged off the coast of Samar, where it fell upon a task group of American escort carriers and their destroyer and destroyer escort screen. Alabama reversed her course and headed for Samar to assist the greatly outnumbered American forces, but the Japanese had retreated by the time she reached the scene. She then joined the protective screen for the Essex task group to hit enemy forces in the central Philippines before retiring to Ulithi on 30 October 1944 for replenishment.

Underway again on 3 November 1944, Alabama screened the fast carriers as they carried out sustained strikes against Japanese airfields, and installations on Luzon to prepare for a landing on Mindoro Island. She spent the next few weeks engaged in operatins against the Visayas and Luzon before retiring to Ulithi on 24 November.

The first half of December 1944 found Alabama engaged in various training exercises and maintenance routines. She left Ulithi on 10 December, and reached the launching point for air strikes on Luzon on 14 December, as the fast carrier task forces launched aircraft to carry out preliminary strikes on airfields on Luzon that could threaten the landings slated to take place on Mindoro. From 14 to 16 December, a veritable umbrella of carrier aircraft covered the Luzon fields, preventing any enemy planes from getting airborne to challenge the Mindoro-bound convoys. Having completed her mission, she left the area to refuel on 17 December; but, as she reached the fueling rendezvous, began encountering heavy weather. By daybreak on the 18th, rough seas and harrowing conditions rendered a fueling at sea impossible; 50 knot winds caused ships to roll heavily. Alabama experienced rolls of 30 degrees, had both her Vought "Kingfisher" floatplanes so badly damaged that they were of no further value, and received minor damage to her structure. At one point in the typhoon, Alabama, recorded wind gusts up to 83 knots. Three destroyers, Hull (DD-350), Mcmagkan (DD-354), and Spence (DD-512), were lost to the typhoon. By 19 December, the storm had run its course; and Alabama, arrived back at Ulithi on 24 December. After pausing there briefly, Alabama continued on to Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, for overhaul.

The battleship entered drydock on 18 January 1945, and remained there until 25 February. Work continued until 17 March, when Alabama got underway for standardization trials and refresher training along the southern California coast. She got underway for Pearl Harbor on 4 April, arrived there on 10 April, and held a week of training exercises. She then continued on to Ulithi and moored there on 28 April 1945.

Alabama departed Ulithi with TF 58 on 9 May 1945, bound for the Ryukyus, to support forces which had landed on Okinawa on 1 April 1945, and to protect the fast carriers as they launched air strikes on installations in the Ryukyus and on Kyushu. On 14 May, several Japanese planes penetrated the combat air patrol to get at the carriers; one crashed Vice Admiral Mitscher's flagship. Alabama's guns splashed two, and assisted in splashing two more.

Subsequently, Alabama rode out a typhoon,on 4 and 5 June, suffering only superficial damage while the nearby heavy cruiser Pittsburgh (CA-70) lost her bow. Alabama subsequently bombarded the Japanese island of Minami Daito Shima, with other fast battleships, on 10 June 1945 and then headed for Leyte Gulf later in June to prepare to strike at the heart of Japan with the 3d Fleet.

On 1 July 1945, Alabama and other 3d Fleet units got underway for the Japanese home islands. Throughout the month of July 1945, Alabama carried out strikes on targets in industrial areas of Tokyo and other points on Honshu, Hokkaido, and Kyushu; on the night of 17 and 18 July, Alabama, and other fast battleships in the task group, carried put the first night bombardment of six major industrial plants in the Hitachi-Mito area of Honshu, about eight miles northeast of Tokyo. On board Alabama to observe the operation was retired Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd, the famed polar explorer.

On 9 August, Alabama transferred a medical party to the destroyer Ault (DD-698), for further transfer to the destroyer Borie (DD-704). The latter had been kamikazied on that date and required prompt medical aid on her distant picket station.

The end of the war found Alabama still at sea, operating off the southern coast of Honshu. On 15 August 1945, she received word of the Japanese capitulation. During the initial occupation of the Yokosuka-Tokyo area, Alabama tranferred detachments of marines and bluejackets for temporary duty ashore; her bluejackets were among the first from the fleet to land. She also served in the screen of the carriers as they conducted reconnaissance flights to locate prisoner-of-war camps.

Alabama entered Tokyo Bay on 5 September to receive men who had served with the occupation forces, and then departed Japanese waters on 20 September. At Okinawa, she embarked 700 sailors—principally members of Navy construction battalions (or "Seabees")—for her part in the "Magic Carpet" operations. She reached San Francisco at mid-day on 15 October, and on Navy Day (27 October 1945) hosted 9,000 visitors. She then shifted to San Pedro, Calif., on 29 October. Alabama remained at San Pedro through 27 February 1946, when she left for the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard for inactivation overhaul. Alabama was decommissioned on 9 January 1947, at the Naval Station, Seattle, and was assigned to the Bremerton Group, United States Pacific Reserve Fleet. She remained there until struck from the Naval Vessel Register on 1 June 1962.

Citizens of the state of Alabama had formed the "USS Alabama Battleship Commission" to raise funds for the preservation of Alabama as a memorial to the men and women who served in World War II. The ship was awarded to that state on 16 June 1964, and was formally turned over on 7 July 1964 in ceremonies at Seattle. Alabama was then towed to her permanent berth at Mobile, Ala., arriving in Mobile Bay on 14 September 1964.

Alabama received nine battle stars for her World War II service.

Take a 16 minute virtual tour below from wargaming.net.