ADMIRAL RAPHAEL SEMMES CAMP #11

SONS OF CONFEDERATE VETERANS

MOBILE, ALABAMA

Battles of Mobile

Brief summaries of the battles are given below. For a more extensive description with photos and an interactive map, check out the article "Fort Blakeley, AL -The Last Battle of the Civil War."

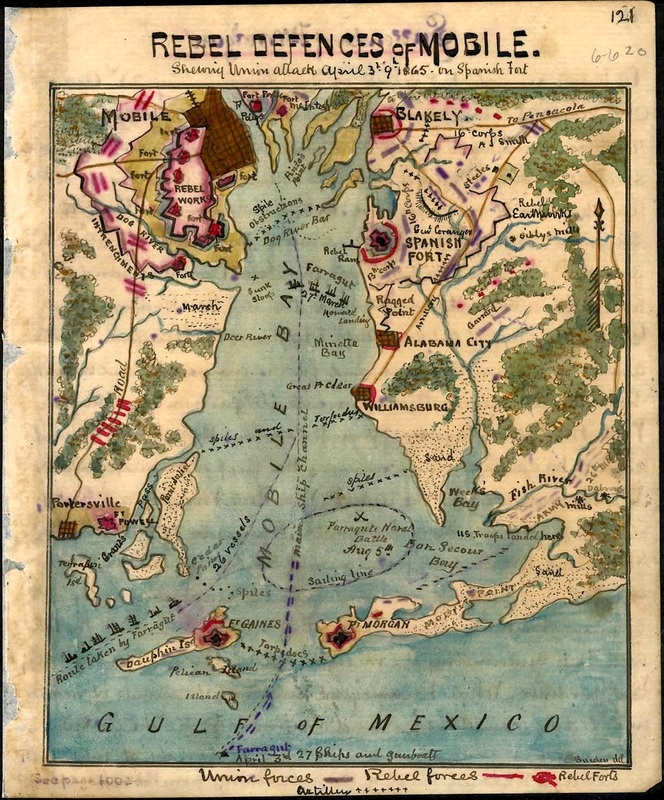

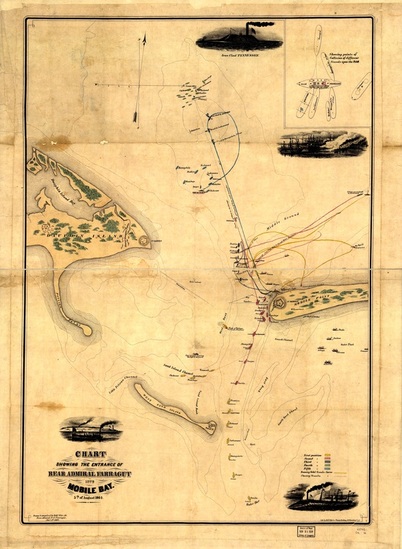

BATTLE OF MOBILE BAY

A print of Battle of Mobile Bay ... Passing Fort Morgan and the Torpedoes, painted by J. O. Davidson in 1886. The scene depicts the sinking of the ironclad USS Tecumseh. Confederate ironclads Morgan, Gaines, and Tennessee approach from the left, and Union ironclads Manhattan and Winnebago approach from behind.

The Battle of Mobile Bay, which took place in August 1864, was the last major naval engagement of the Civil War, and the Union victory there led to the closing of the Mobile port. The action is best remembered for the famous quotation, "Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!" attributed to Union Adm. David Glasgow Farragut, and the massive resistance against overwhelming odds put forth by the Confederates and the ironclad CSS Nashville as they defended the bay and Forts Morgan and Gaine

By the summer of 1864 the Civil War was entering into its fourth year, and although Confederate forces had suffered devastating defeats in 1863, the South's prospects for independence remained hopeful. Southern agriculture was bountiful and southern cities and ports thrived, despite the Union blockade. As Union general Ulysses S. Grant engaged Confederate general Robert E. Lee in the "Overland Campaign," Union forces under David G. Farragut maneuvered toward Mobile Bay. At that time Mobile remained the last major Confederate port not taken by Union forces and became a key element in the North's strategic war aims. Union victory in Mobile Bay would provide a much-needed boost to northern morale, boost President Abraham Lincoln's popularity, and provide the North with a point of entry for future operations into the Deep South. Moreover, Union capture of the bay would cut off Confederate blockade runners, thus hindering the South's economy.

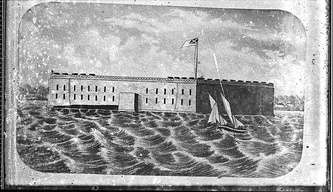

Mobile Bay was one of the most well-defended of southern ports. The main entrance was flanked by two substantial fortifications, Fort Morgan on Mobile Point and Fort Gaines on Dauphin Island, both defended by impressive artillery batteries of 47 and 16 guns, respectively. In addition, the channel was protected with a triple line of mines, commonly called torpedoes at the time, that were suspended below the surface and could sink or cripple any ship that hit one of them. The city of Mobile, strategically significant as a rail center and port, was equally well defended. In 1862 Confederate forces had begun constructing a formidable line of entrenchments (earthen fortifications to protect the position and soldiers against enemy fire), which by 1864 had developed into a triple line of entrenchments, one behind the other, against attack by land forces. These fortifications, in addition to the protection from the harbor, prevented Union forces from closing to within effective shelling range.

Union commanders realized that any infantry assault against the city would be disastrous and consequently made plans to capture the bay first, and then compel the city's populace to evacuate. Farragut, a Tennessee native who became a midshipman at age nine, planned to storm past the forts into the bay, directly engage the Confederate fleet, neutralize the forts, and gain possession of Mobile Bay. His plan was risky because in addition to the two forts, a small Confederate fleet, commanded by Adm. Franklin Buchanan, consisting of three gunboats and one ironclad ram guarded Mobile Bay. Farragut, with 18 ships, including gunboats, sloops, and ironclads, gave little consideration to the lightly armed gunboats, Franklin Buchananthe CSS Selma, the CSS Morgan, and the CSS Gaines, because he was confident that his fleet could quickly overwhelm them. Of greater concern was the CSSTennessee, which was commissioned in February 1864 and boasted two 7-inch and four 6.4-inch, long-range Brooke rifles. In addition, Farragut was worried about the ironclad ram CSS Nashville, but that ship was under-armored and under-gunned and remained up river near Mobile, unbeknownst to the admiral. Thus theTennessee was Buchanan's best defense against Farragut's fleet. To direct attention away from his main assault, Farragut ordered 2,000 infantry soldiers to assail nearby Dauphin Island and eventually to press to Fort Gaines on August 3.

Mobile Bay was one of the most well-defended of southern ports. The main entrance was flanked by two substantial fortifications, Fort Morgan on Mobile Point and Fort Gaines on Dauphin Island, both defended by impressive artillery batteries of 47 and 16 guns, respectively. In addition, the channel was protected with a triple line of mines, commonly called torpedoes at the time, that were suspended below the surface and could sink or cripple any ship that hit one of them. The city of Mobile, strategically significant as a rail center and port, was equally well defended. In 1862 Confederate forces had begun constructing a formidable line of entrenchments (earthen fortifications to protect the position and soldiers against enemy fire), which by 1864 had developed into a triple line of entrenchments, one behind the other, against attack by land forces. These fortifications, in addition to the protection from the harbor, prevented Union forces from closing to within effective shelling range.

Union commanders realized that any infantry assault against the city would be disastrous and consequently made plans to capture the bay first, and then compel the city's populace to evacuate. Farragut, a Tennessee native who became a midshipman at age nine, planned to storm past the forts into the bay, directly engage the Confederate fleet, neutralize the forts, and gain possession of Mobile Bay. His plan was risky because in addition to the two forts, a small Confederate fleet, commanded by Adm. Franklin Buchanan, consisting of three gunboats and one ironclad ram guarded Mobile Bay. Farragut, with 18 ships, including gunboats, sloops, and ironclads, gave little consideration to the lightly armed gunboats, Franklin Buchananthe CSS Selma, the CSS Morgan, and the CSS Gaines, because he was confident that his fleet could quickly overwhelm them. Of greater concern was the CSSTennessee, which was commissioned in February 1864 and boasted two 7-inch and four 6.4-inch, long-range Brooke rifles. In addition, Farragut was worried about the ironclad ram CSS Nashville, but that ship was under-armored and under-gunned and remained up river near Mobile, unbeknownst to the admiral. Thus theTennessee was Buchanan's best defense against Farragut's fleet. To direct attention away from his main assault, Farragut ordered 2,000 infantry soldiers to assail nearby Dauphin Island and eventually to press to Fort Gaines on August 3.

first hand account of the engineer abord the CSS Tneeessee

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

Invasion of Mobile bay

The Battle of Mobile Bay began on the morning of August 5 when Confederate guns from Fort Morgan opened fire on Farragut's advancing fleet. Early action favored the Confederates when the ironclad monitor USSTecumseh hit a torpedo, sinking to the bottom of the bay with 94 men. Farragut had tied himself to the rigging of the USS Hartford to better observe and direct the battle and reportedly exclaimed, "Damn the Torpedoes! Full speed ahead!"

USS TennesseeAs expected, Union forces quickly neutralized the Confederate gunboats, and the Tennesseeremained the only threat. The ship engaged 14 of Farragut's wooden vessels, but the ram's mobility was limited, and she struggled to hold off the Union gunboats. Buchanan remained convinced that the Tennessee's armor would withstand contact and fire from the Federal vessels. At 9:35 a.m., however, the Tennessee fired its last shot into the hull of the Hartford. Intense firing and ramming by Union gunboats had wrought havoc on the Tennessee, jamming shut four of the 10 port shutters and destroying the smokestack and steering chains. Buchanan was wounded as iron fragments from an exploding shell smashed into his leg. At about 10:00 a.m., he surrendered the Tennessee and her 190-man crew.

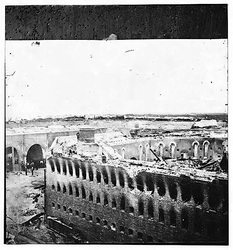

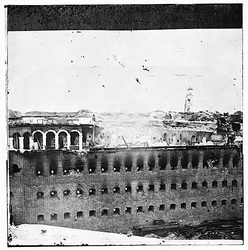

Farragut's fleet seemingly had accomplished the impossible: racing past the forts, skillfully navigating the torpedo mines, and capturing the Confederacy's most powerful ship. Farragut's successful offensive into the bay cost him 315 casualties, compared with only 32 casualties among Confederate sailors. But before the Union could declare a complete victory,Gordon GrangerForts Morgan and Gaines had to be captured. That task fell to Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger's infantry division. In a combined offensive, Farragut's ships and Granger's artillery began bombarding Fort Gaines, and on August 8 at 9:30 a.m., Col. Charles Anderson of the Confederate Army surrendered the fort. The Union Army took possession of 800 prisoners. Brig. Gen. Richard Page, commanding officer of Fort Morgan, remained determined to hold fast, however. When Union forces demanded his surrender, Morgan replied, "I am prepared to sacrifice life and will only surrender when I have no means of defense." Union guns began bombarding the fort on August 22, and on the following day Page, determining that he no longer had a "means of defense," surrendered the fort, along with 600 men. The Union captured about 100 total pieces of artillery from the Confederate forts.

Farragut's capture of Mobile Bay was a decisive strategic victory for the Union. His success was the first significant victory in the Union's 1864 offensives and provided a much-needed boost to northern morale. Although the city of Mobile remained in Confederate hands until the final days of the war, the port was closed to Confederate blockade runners, thus cutting off supply lines. On March 24, 1865, Maj. Gen. Dabney Herdon Maury and the remnants of his army evacuated Mobile, and the city surrendered on April 12, exactly four years after the start of the Civil War at Fort Sumter.

Additional Resources

Friend, Jack. West Wind, Flood Tide: The Battle of Mobile Bay. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2004.

Hearn, Chester G. Mobile Bay and the Mobile Campaign: The Last Great Battles of the Civil War. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 1993.

Waugh, John C., and Grady McWhiney. Last Stand at Mobile. Abilene: McWhiney Foundation Press, 2002.

Material from the Encyclopedia of Alabama.

USS TennesseeAs expected, Union forces quickly neutralized the Confederate gunboats, and the Tennesseeremained the only threat. The ship engaged 14 of Farragut's wooden vessels, but the ram's mobility was limited, and she struggled to hold off the Union gunboats. Buchanan remained convinced that the Tennessee's armor would withstand contact and fire from the Federal vessels. At 9:35 a.m., however, the Tennessee fired its last shot into the hull of the Hartford. Intense firing and ramming by Union gunboats had wrought havoc on the Tennessee, jamming shut four of the 10 port shutters and destroying the smokestack and steering chains. Buchanan was wounded as iron fragments from an exploding shell smashed into his leg. At about 10:00 a.m., he surrendered the Tennessee and her 190-man crew.

Farragut's fleet seemingly had accomplished the impossible: racing past the forts, skillfully navigating the torpedo mines, and capturing the Confederacy's most powerful ship. Farragut's successful offensive into the bay cost him 315 casualties, compared with only 32 casualties among Confederate sailors. But before the Union could declare a complete victory,Gordon GrangerForts Morgan and Gaines had to be captured. That task fell to Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger's infantry division. In a combined offensive, Farragut's ships and Granger's artillery began bombarding Fort Gaines, and on August 8 at 9:30 a.m., Col. Charles Anderson of the Confederate Army surrendered the fort. The Union Army took possession of 800 prisoners. Brig. Gen. Richard Page, commanding officer of Fort Morgan, remained determined to hold fast, however. When Union forces demanded his surrender, Morgan replied, "I am prepared to sacrifice life and will only surrender when I have no means of defense." Union guns began bombarding the fort on August 22, and on the following day Page, determining that he no longer had a "means of defense," surrendered the fort, along with 600 men. The Union captured about 100 total pieces of artillery from the Confederate forts.

Farragut's capture of Mobile Bay was a decisive strategic victory for the Union. His success was the first significant victory in the Union's 1864 offensives and provided a much-needed boost to northern morale. Although the city of Mobile remained in Confederate hands until the final days of the war, the port was closed to Confederate blockade runners, thus cutting off supply lines. On March 24, 1865, Maj. Gen. Dabney Herdon Maury and the remnants of his army evacuated Mobile, and the city surrendered on April 12, exactly four years after the start of the Civil War at Fort Sumter.

Additional Resources

Friend, Jack. West Wind, Flood Tide: The Battle of Mobile Bay. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2004.

Hearn, Chester G. Mobile Bay and the Mobile Campaign: The Last Great Battles of the Civil War. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 1993.

Waugh, John C., and Grady McWhiney. Last Stand at Mobile. Abilene: McWhiney Foundation Press, 2002.

Material from the Encyclopedia of Alabama.

official us version

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

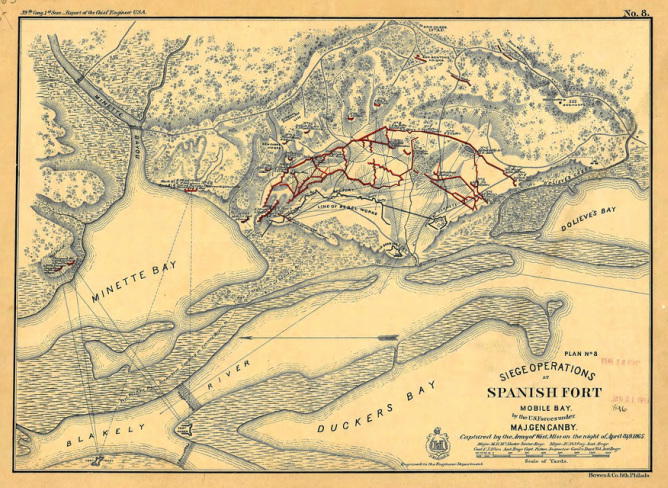

seige of the eastern shore

Battle of fort mcdermott

A Union attack on the fortifications began on 27 Mar 1865 and lasted for 13 days. The Union troops numbered about 30,000 against some 2,500 Confederate troops. The fortifications were abandoned by the confederate defenders on the night of 8-9 Apr 1865. Most of the Confederate troops fled across the river and toward Fort Blakeley and when Union troops stormed the fortifications on the 9th they found empty positions and spiked guns. The U.S. Civil War effectively ended on that same day with General Robert E. Lee surrendering at Appomattox Court House around 4 pm. The battle at Spanish Fort shifted to the Battle at Fort Blakeley later that day.

For further reading, check HERE

For further reading, check HERE

battle of fort blakeley

Battle of Fort Bakeley fought April 2, 1865–April 9, 1865

Maj. Gen. Edward Canby's Union forces, the XVI and XIII Corps, moved along the eastern shore of Mobile Bay, forcing the Confederates back into their defenses. Union forces then concentrated on Spanish Fort, Alabama and nearby Fort Blakely. By April 1, Union forces had enveloped Spanish Fort, thereby releasing more troops to focus on Fort Blakely. Confederate Brig. Gen. St. John R. Liddell, with about 4,000 men, held out against the much larger Union force until Spanish Fort fell on April 8 in the Battle of Spanish Fort. This allowed Canby to concentrate 16,000 men for the attack on April 9, led by Brig. Gen. John P. Hawkins. Sheer numbers breached the Confederate earthworks, compelling the Confederates, including Liddell, to surrender. The siege and capture of Fort Blakely was basically the last combined-force battle of the war. Yet, it is criticized by some (such as Ulysses S. Grant) as an ineffective contribution to Union war effort due to Canby's lateness in engaging his troops. African-American forces played a major role in the successful Union assault.

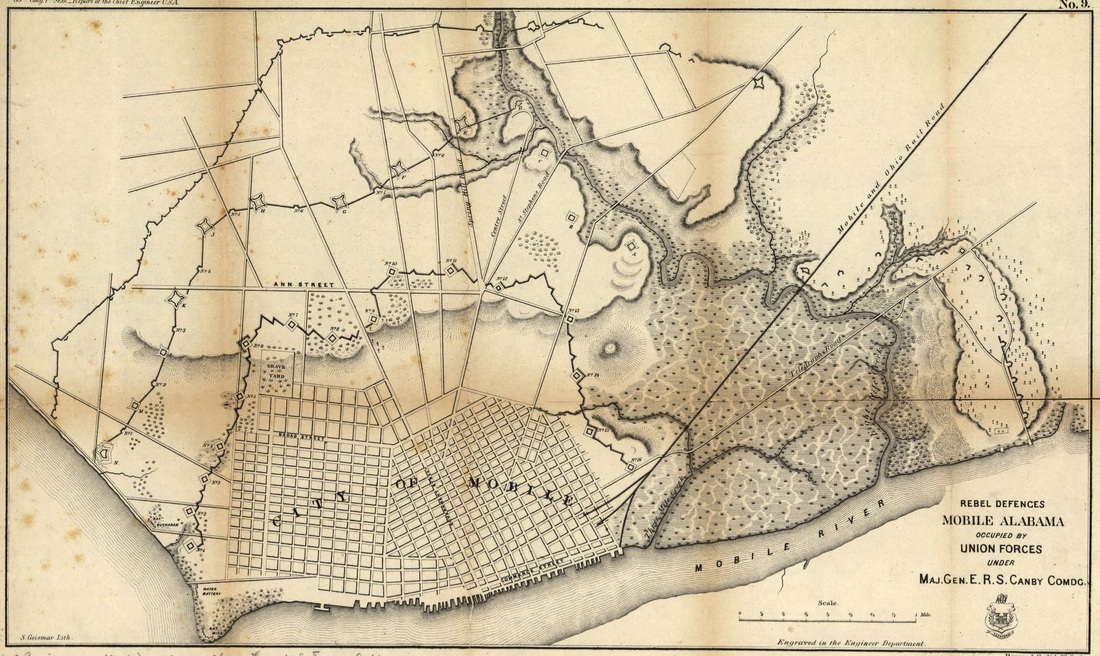

Plan of defenses around the city of mobile, 1865

The defenses were never needed as the city fell quietly on 12 April, 1865. This map was obtained from the Library of Congress. Another, more detailed and higher resolution map may be explored at the David Rumsey Map Collection. The map's description and legend may be found at the Harvard College Library Digital Map Collection.

Major General Dabney Herndon Maury –

Defender of the City of mobile

Major-General Dabney Herndon Maury was born at Fredericksburg, Va., May 20, 1822, the son of Capt. John Minor Maury, United States navy, whose wife was the daughter of Fontaine Maury. His descent is from the old Virginia families of Brooke and Minor, and the Huguenot emigrees, the Fontaines and Maurys. He was educated at the classical school of Thomas Harrison, Fredericksburg, studied law at the university of Virginia, and was graduated at West Point in 1846, with the rank of brevet second lieutenant in the mounted rifles.

A theater for active service in his profession was awaiting him in Mexico, where he was at once ordered. He conducted himself with soldierly valor in this war, particularly at the siege of Vera Cruz and the battle of Cerro Gordo, where he was severely wounded, and received the brevet of first lieutenant for gallantry. In further recognition of his services he was presented with a sword by the citizens of Fredericksburg and the legislature of Virginia. For several years subsequent to the Mexican war he was detailed for service at the United States Military Academy, first as assistant professor of geography, history and ethics, and afterward as assistant professor of infantry tactics. In 1852 he was transferred to frontier duty in Texas in which he continued, with promotion to first lieutenant mounted rifles, until 1858, when he was appointed superintendent of the cavalry school at Carlisle, Pa. From April 15, 1860, until the outbreak of the Confederate war he was assistant adjutant-general, with the rank of brevet captain, in New Mexico.

He promptly acted with his State in 1861, and was commissioned captain, corps of cavalry, C. S. A., to date from March 16th. Subsequently he was promoted colonel, was appointed adjutant-general of the army at Manassas, and when Gen. Earl Van Dorn was assigned to command the Trans-Mississippi department, early in 1862, he became his chief of staff and adjutant-general. In his report of the battle of Elkhorn Tavern, General Van Dorn wrote: "Colonel Maury was of invaluable service to me both in preparing for and during the battle. Here, as on other battlefields where I have served with him, he proved to be a zealous patriot and true soldier; cool and calm under all circumstances, he was always ready, either with his sword or pen. "

Maury was promptly promoted brigadier-general. He accompanied Van Dorn to the consultation with A. S. Johnston and Beauregard at Corinth previous to the battle of Shiloh, and subsequently was transferred with the main Confederate force east of the Mississippi, where his service was afterward given. When Price took command of the army of the West at Tupelo, he commanded one of its two divisions, including the brigades of John C. Moore, W. L. Cabell and C. W. Phifer, and the cavalry of F. C. Armstrong. Little of Maryland, commanding the other division, fell at Iuka, where Maury was held in re serve, and afterward served as rear guard, repelling pursuit. About a fortnight later he commanded the center in the battle of Corinth, against Rosecrans, and gallantly engaged the enemy, who was driven from his entrenchments and through the town. During the subsequent retirement he defended the rear, fighting spiritedly at Hatchie's bridge.

He was promoted major-general in November, 1862, and on December 30th, arrived before Vicksburg from Grenada, to support S. D. Lee, who had repulsed Sherman's attack at Chickasaw bayou, and was assigned to command of the right wing. He continued in service here, his troops being engaged at Steele's bayou and in the defeat of the Yazoo Pass expedition, until he was ordered to Knoxville, April 15th, to take command of the department of East Tennessee.

A month later he was transferred to the command of the district of the Gulf. In this region, with headquarters at Mobile, he continued to serve until the end of the war. During the siege of Atlanta, in command of reserve troops, he operated in defense of the Macon road. In August, i864, in spite of a gallant struggle, the defenses of Mobile bay were taken, and in March and April, 1865, Maury, with a garrison about 9,000 strong, defended the city against the assaults of Canby's army of 45,000 until, after heavy loss, he retired without molestation to Meridian. But the war was now practically over, and on May 4th, his forces were included in the general capitulation of General Taylor. Subsequently he made his home at Richmond, Va.

He has given many valuable contributions to the history of the war period, and in 1868 organized the Southern historical society, the collections of which he opened to the government war records office, securing in return free access to that department by ex-Confederates. In 1878 he was a leader in the movement for the reorganization of the volunteer troops of the nation, and until 1880 served as a member of the executive committee of the National Guard association of the United States. In i886 he was appointed United States minister to Columbia, a position he held until June 22, 1889. Since then he has been occupied in literary pursuits, being the author of a school history of Virginia, and other works.

Confederate Military History, Vol. III, pp.636-638.

A theater for active service in his profession was awaiting him in Mexico, where he was at once ordered. He conducted himself with soldierly valor in this war, particularly at the siege of Vera Cruz and the battle of Cerro Gordo, where he was severely wounded, and received the brevet of first lieutenant for gallantry. In further recognition of his services he was presented with a sword by the citizens of Fredericksburg and the legislature of Virginia. For several years subsequent to the Mexican war he was detailed for service at the United States Military Academy, first as assistant professor of geography, history and ethics, and afterward as assistant professor of infantry tactics. In 1852 he was transferred to frontier duty in Texas in which he continued, with promotion to first lieutenant mounted rifles, until 1858, when he was appointed superintendent of the cavalry school at Carlisle, Pa. From April 15, 1860, until the outbreak of the Confederate war he was assistant adjutant-general, with the rank of brevet captain, in New Mexico.

He promptly acted with his State in 1861, and was commissioned captain, corps of cavalry, C. S. A., to date from March 16th. Subsequently he was promoted colonel, was appointed adjutant-general of the army at Manassas, and when Gen. Earl Van Dorn was assigned to command the Trans-Mississippi department, early in 1862, he became his chief of staff and adjutant-general. In his report of the battle of Elkhorn Tavern, General Van Dorn wrote: "Colonel Maury was of invaluable service to me both in preparing for and during the battle. Here, as on other battlefields where I have served with him, he proved to be a zealous patriot and true soldier; cool and calm under all circumstances, he was always ready, either with his sword or pen. "

Maury was promptly promoted brigadier-general. He accompanied Van Dorn to the consultation with A. S. Johnston and Beauregard at Corinth previous to the battle of Shiloh, and subsequently was transferred with the main Confederate force east of the Mississippi, where his service was afterward given. When Price took command of the army of the West at Tupelo, he commanded one of its two divisions, including the brigades of John C. Moore, W. L. Cabell and C. W. Phifer, and the cavalry of F. C. Armstrong. Little of Maryland, commanding the other division, fell at Iuka, where Maury was held in re serve, and afterward served as rear guard, repelling pursuit. About a fortnight later he commanded the center in the battle of Corinth, against Rosecrans, and gallantly engaged the enemy, who was driven from his entrenchments and through the town. During the subsequent retirement he defended the rear, fighting spiritedly at Hatchie's bridge.

He was promoted major-general in November, 1862, and on December 30th, arrived before Vicksburg from Grenada, to support S. D. Lee, who had repulsed Sherman's attack at Chickasaw bayou, and was assigned to command of the right wing. He continued in service here, his troops being engaged at Steele's bayou and in the defeat of the Yazoo Pass expedition, until he was ordered to Knoxville, April 15th, to take command of the department of East Tennessee.

A month later he was transferred to the command of the district of the Gulf. In this region, with headquarters at Mobile, he continued to serve until the end of the war. During the siege of Atlanta, in command of reserve troops, he operated in defense of the Macon road. In August, i864, in spite of a gallant struggle, the defenses of Mobile bay were taken, and in March and April, 1865, Maury, with a garrison about 9,000 strong, defended the city against the assaults of Canby's army of 45,000 until, after heavy loss, he retired without molestation to Meridian. But the war was now practically over, and on May 4th, his forces were included in the general capitulation of General Taylor. Subsequently he made his home at Richmond, Va.

He has given many valuable contributions to the history of the war period, and in 1868 organized the Southern historical society, the collections of which he opened to the government war records office, securing in return free access to that department by ex-Confederates. In 1878 he was a leader in the movement for the reorganization of the volunteer troops of the nation, and until 1880 served as a member of the executive committee of the National Guard association of the United States. In i886 he was appointed United States minister to Columbia, a position he held until June 22, 1889. Since then he has been occupied in literary pursuits, being the author of a school history of Virginia, and other works.

Confederate Military History, Vol. III, pp.636-638.

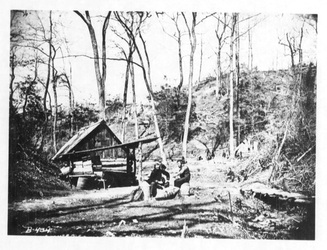

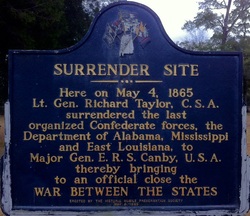

official end of hostilities

It is a recorded fact that the last surrender of the Confederate Army, east of the Mississippi River, occurred in Citronelle, Alabama on May 4, 1865. The closing scenes of that awful bloody drama, the Civil War, were witnessed in this vicinity. Lee and Johnson had surrendered; Mobile had been occupied by Union forces after the Battle of Mobile Bay, and but one organized body of Confederates that could be called an army, remained in the field. This last army of close to 9,000 Confederate soldiers was surrendered on the 4th of May, 1865 by its Commander, General Richard (Dick) Taylor, to the U.S. Army General, E.R.S. Canby. A memorial marker has been placed at this spot near a large white oak tree by the Historical Mobile Preservation Society on May 4, 1965. The original “Surrender Oak” was blown down in the hurricane of 1906. From it was made numerous walking canes, gavels, and other items as souvenirs; most of which have long since disappeared, with the exception of several which were sent to the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, DC.

The Citronelle Historical Preservation Society hosts the Surrender Oak Festival each year on the first Saturday in May at the Citronelle Depot Museum.

The Citronelle Historical Preservation Society hosts the Surrender Oak Festival each year on the first Saturday in May at the Citronelle Depot Museum.

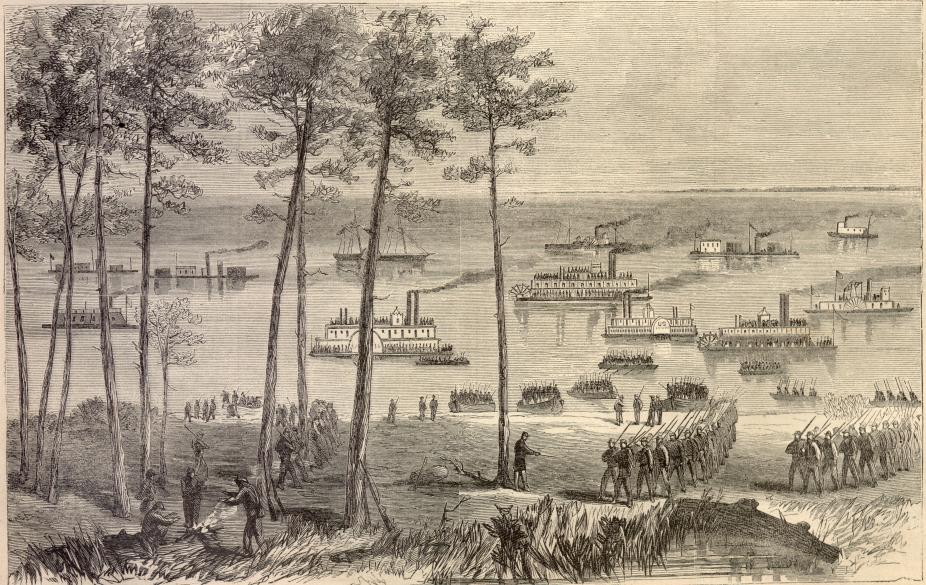

THE FIGHT for MOBILE

As Reported in Harper’s Weekly 29 April 1965

"On the 20th of March the Sixteenth Corps, under General A. J. Smith, left Dauphin on twenty transports, accompanied by gun-boats, and proceeded up an arm of Mobile Bay to the mouth of Fish River, where the troops were landed at Dauley's Mills. The Thirteenth Corps, under General Granger, left Fort Morgan, and on the 21st of March went into camp on the left of Smith, resting its left wing on Mobile Bay. Three days afterward this corps was followed by General Knipe with 6000 cavalry. On the 25th the Federal line was pushed forward so as to extend from Alabama City on the bay to Deer Park."

Battle of Spanish Fort (Fort McDermott)

"The first point of attack was Spanish Fort, which is directly opposite Mobile, and is the latest built and strongest of the defenses of that city. It guards the eastern channel of the bay. On the 27th the bombardment commenced. In the mean time the Monitors and gunboats were laboring hard to overcome the obstructions. They had succeeded so far that the Monitors Milwaukee, Winnebago, Kickapoo, and the Monitor ram Osage moved in line to attack at 3 P.M. An hour afterward a torpedo exploded. under the Milwaukee, and she immediately filled and sunk in eleven feet of water. There were no casualties. There was steady firing all night and the next day. At about 2 o'clock P.M. on the 29th a torpedo struck the port bow of the Osage and exploded, tearing away the plating and timbers, killing two men and wounding several others. We give on page 268 an engraving illustrating the nature of the torpedoes found in the Bay. Those given in the sketch are those with the mushroom-shaped anchor. The slightest pressure causes explosion."

"On the 8th of April an extraordinary force was brought to bear upon Spanish Fort. Twenty-two Parrott guns were got within half a mile of the work, while other powerful batteries were still nearer. Two gun-boats joined in the tremendous cannonade. The result was that the fort surrendered a little after midnight. Fort Alexandria followed, and the guns of these two were turned against Forts Tracy and Huger, in the harbor, at the mouth of the Blakely and Appalachee rivers. But these had already been abandoned. The Monitors then went busily to work removing torpedoes, and ran up to within shelling distance of the city."

Battle of Fort Blakeley

"The Battle Shortly after the capture of Spanish Fort, intelligence of the capture and the fall of Richmond was read to the troops, in connection with orders to attack Fort Blakely. Several batteries of artillery, and large quantities of ammunition were taken with the fort, besides 2400 prisoners. Our loss in the whole affair was much less than 2000 killed and wounded, and none missing. Seven hundred prisoners were taken with Spanish Fort. Mobile was occupied by the national forces on the 12th."

In another section of the magazine:

"We have already, in a previous number, described the assault on Fort Blakeley, which we illustrate this week on this page. Probably the last charge of this war, it was as gallant as any on record. Fort Blakeley formed the left of the rebel line of works defending Mobile. The approach to the work was impeded by obstructions of every sort, which the national troops were fully one hour in making their w a y through. The loss here was great..."

"The first point of attack was Spanish Fort, which is directly opposite Mobile, and is the latest built and strongest of the defenses of that city. It guards the eastern channel of the bay. On the 27th the bombardment commenced. In the mean time the Monitors and gunboats were laboring hard to overcome the obstructions. They had succeeded so far that the Monitors Milwaukee, Winnebago, Kickapoo, and the Monitor ram Osage moved in line to attack at 3 P.M. An hour afterward a torpedo exploded. under the Milwaukee, and she immediately filled and sunk in eleven feet of water. There were no casualties. There was steady firing all night and the next day. At about 2 o'clock P.M. on the 29th a torpedo struck the port bow of the Osage and exploded, tearing away the plating and timbers, killing two men and wounding several others. We give on page 268 an engraving illustrating the nature of the torpedoes found in the Bay. Those given in the sketch are those with the mushroom-shaped anchor. The slightest pressure causes explosion."

"On the 8th of April an extraordinary force was brought to bear upon Spanish Fort. Twenty-two Parrott guns were got within half a mile of the work, while other powerful batteries were still nearer. Two gun-boats joined in the tremendous cannonade. The result was that the fort surrendered a little after midnight. Fort Alexandria followed, and the guns of these two were turned against Forts Tracy and Huger, in the harbor, at the mouth of the Blakely and Appalachee rivers. But these had already been abandoned. The Monitors then went busily to work removing torpedoes, and ran up to within shelling distance of the city."

Battle of Fort Blakeley

"The Battle Shortly after the capture of Spanish Fort, intelligence of the capture and the fall of Richmond was read to the troops, in connection with orders to attack Fort Blakely. Several batteries of artillery, and large quantities of ammunition were taken with the fort, besides 2400 prisoners. Our loss in the whole affair was much less than 2000 killed and wounded, and none missing. Seven hundred prisoners were taken with Spanish Fort. Mobile was occupied by the national forces on the 12th."

In another section of the magazine:

"We have already, in a previous number, described the assault on Fort Blakeley, which we illustrate this week on this page. Probably the last charge of this war, it was as gallant as any on record. Fort Blakeley formed the left of the rebel line of works defending Mobile. The approach to the work was impeded by obstructions of every sort, which the national troops were fully one hour in making their w a y through. The loss here was great..."